Moving abroad? Without proper financial preparation, you could face serious challenges like tax penalties, frozen accounts, or healthcare gaps. Here’s what you need to know before you go:

- Taxes: U.S. citizens must file taxes on worldwide income and understand how tax residency affects their reporting obligations. Use tools like the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (up to $130,000 for 2025) to reduce or eliminate tax liability.

- Banking: Close unnecessary accounts and check if your U.S. bank supports non-resident addresses. Open an offshore account early to avoid delays.

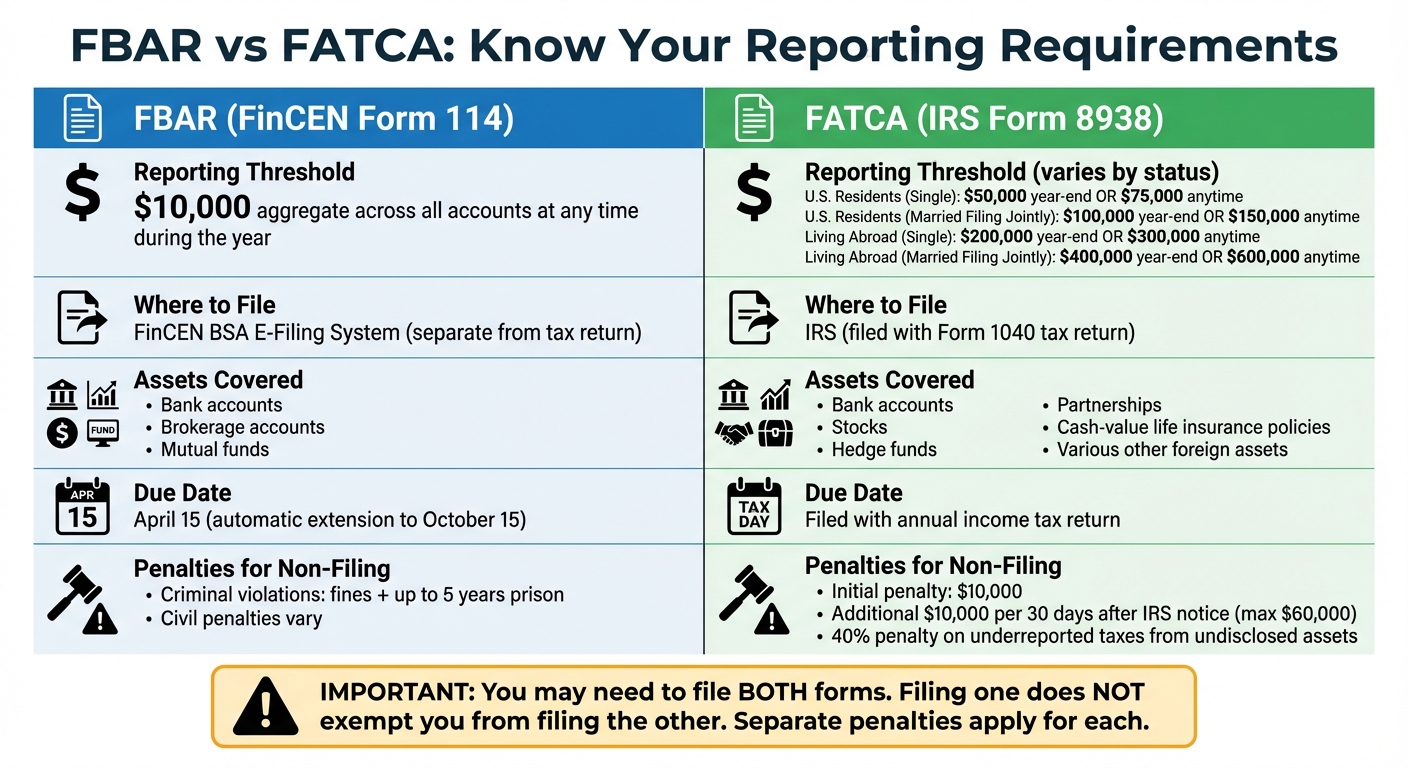

- Foreign Reporting: File FBAR (if foreign accounts exceed $10,000) and FATCA (if foreign assets exceed $50,000–$600,000, depending on status).

- Investments: Avoid foreign mutual funds due to high U.S. taxes. Stick to U.S.-based accounts with expat-friendly custodians like Schwab or Fidelity.

- Retirement Accounts: Understand how your destination treats IRAs and Roth IRAs. Plan contributions carefully to stay compliant.

- Healthcare: Medicare doesn’t cover expenses abroad. Get international health insurance and digitize medical records.

- Exit Tax: Renouncing U.S. citizenship? Plan for the exit tax, which applies to assets over $2 million or unrealized gains above $910,000 (2026).

Handle these steps before leaving to avoid costly mistakes and ensure a smooth transition.

Understanding Your Tax Residency and Filing Requirements

If you’re planning to move abroad, it’s crucial to get a handle on your tax obligations before you leave. Here’s an important fact: the U.S. taxes its citizens on worldwide income. That means if you’re a U.S. citizen or green card holder, you’re required to file a tax return no matter where you live. For green card holders, formally surrendering your status with Form I-407 is necessary if you want to change your tax obligations.

How the IRS Determines Tax Residency

The IRS uses two main tests to determine tax residency:

- Green Card Test: If you’re a lawful permanent resident, you’re automatically considered a tax resident.

- Substantial Presence Test: This test looks at how many days you’ve spent in the U.S. It counts all 31 days in the current year, plus a weighted total of 183 days over the past three years (100% of the current year, 33.3% of the previous year, and 16.6% of the year before that).

For expats looking to claim the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion, you’ll need to meet one of these:

- Bona Fide Residence Test: This considers your residential ties and whether you’ve committed to a full tax year abroad.

- Physical Presence Test: You must be physically present in a foreign country for at least 330 full days during any 12-month period.

Be consistent with your claims to foreign tax authorities – conflicting statements could lead to the denial of these exclusions.

U.S. Tax Filing Requirements for Expats

Once you’ve established your tax residency, you’ll need to ensure your filing meets the required thresholds and deadlines. For 2024, here’s when you need to file:

- If your worldwide gross income exceeds $14,600 (single filers) or $29,200 (married filing jointly).

- If you’re self-employed and your net earnings are $400 or more.

Expats automatically get a two-month extension, pushing the filing deadline from April 15 to June 15. Need more time? Submit Form 4868 by June 15 to extend your deadline to October 15. But remember, extensions only give you more time to file – not to pay. Any unpaid taxes will start accruing interest from April 15.

To take advantage of tax benefits like the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (Form 2555) or the Foreign Tax Credit (Form 1116), you must file a return.

"If you’re a U.S. citizen or resident alien, the rules for filing income tax returns and paying estimated tax are generally the same whether you’re in the United States or abroad. No matter where you live, your worldwide income is subject to U.S. tax".

| Filing Requirement | Form | Deadline (for expats) | Key Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Income Tax Return | Form 1040 | June 15 | $14,600 (single), $29,200 (married filing jointly) |

| Foreign Earned Income Exclusion | Form 2555 | Filed with Form 1040 | Must meet residency tests |

| Extended Filing Deadline | Form 4868 | June 15 (to extend to October 15) | – |

| Self-Employment Tax | Schedule SE | Filed with Form 1040 | $400 net earnings |

Lastly, keep in mind that unpaid tax debt could lead to the IRS notifying the State Department, which might impact your passport.

Meeting Foreign Account Reporting Requirements (FBAR and FATCA)

Once you establish U.S. tax residency, it’s crucial to understand digital nomad taxes and report all foreign financial accounts to comply with federal laws. This step isn’t just about following the rules – it’s about protecting your assets and avoiding hefty penalties. The U.S. government requires separate filings under FBAR and FATCA for foreign accounts, and failing to meet these obligations can lead to serious consequences.

FBAR: How to Report Foreign Bank Accounts

FBAR, or FinCEN Form 114, applies to U.S. persons – whether you’re a citizen, resident, or domestic entity – who have a financial interest in or signature authority over foreign financial accounts. If the combined value of these accounts exceeds $10,000 at any point during the calendar year, you’re required to file. Keep in mind, the $10,000 threshold is the total value across all accounts, not just individual ones.

FBAR reporting covers a range of accounts, including bank accounts, brokerage accounts, and mutual funds. If you own a joint account, each account holder must report its full value.

You must file your FBAR electronically through the FinCEN BSA E-Filing System. The deadline is April 15, with an automatic extension to October 15. Additionally, you’re required to keep records of your foreign accounts for at least five years. These records should include details like account numbers, bank names and addresses, account types, and maximum values.

If you missed filing an FBAR, submit it as soon as possible along with an explanation. The IRS may waive penalties if you can show reasonable cause and have correctly reported any income tied to the accounts. However, criminal violations could lead to fines and even prison time of up to five years.

While FBAR focuses on financial accounts, FATCA expands reporting to other foreign assets.

FATCA: Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act Requirements

FATCA, or Form 8938, goes beyond bank accounts to include a broader range of foreign assets. This includes stocks, partnerships, hedge funds, and even cash-value life insurance policies. Unlike FBAR, FATCA is filed directly with your annual tax return (Form 1040).

The reporting thresholds for FATCA depend on your residency and filing status. For U.S. residents filing as single, you must report if your foreign assets exceed $50,000 on the last day of the year or $75,000 at any point during the year. For married couples filing jointly, the thresholds rise to $100,000 at year-end or $150,000 at any time. If you live abroad, the limits are higher – $200,000 at year-end or $300,000 at any time for single filers, and $400,000 at year-end or $600,000 at any time for married couples filing jointly.

| Feature | FBAR (FinCEN Form 114) | FATCA (IRS Form 8938) |

|---|---|---|

| Reporting Threshold | $10,000 aggregate at any time | $50,000–$600,000 (varies by filing status and residency) |

| Where to File | FinCEN (BSA E-Filing System) | IRS (with Form 1040) |

| Assets Covered | Bank accounts, brokerage accounts, mutual funds | Various assets including accounts, stocks, hedge funds, and certain insurance policies |

| Due Date | April 15 (automatic extension to October 15) | Filed with the annual income tax return |

Failing to comply with FATCA can be costly. If you don’t file Form 8938, you face an initial penalty of $10,000, with an additional $10,000 for every 30 days of non-filing after receiving an IRS notice – up to a maximum of $60,000. On top of that, underreported taxes tied to undisclosed foreign assets could incur a 40% penalty.

"Taxpayers with foreign financial accounts may have to report information under both FATCA and Bank Secrecy Act regulations (FBAR). Separate penalties may apply for failing to file each form."

FBAR and FATCA serve different purposes, and filing one doesn’t exempt you from filing the other. Take the time to understand which forms apply to your situation to avoid complications later. Each requirement has its own scope and process, so make sure you’re fully prepared before you leave your home country.

Reorganizing Your Banking and Financial Accounts

Once you’ve met your reporting obligations, it’s time to streamline your banking setup. Holding onto unnecessary accounts when leaving your home country can lead to avoidable headaches, like hidden fees or even frozen accounts. The goal here is simple: keep only the accounts you truly need and close the rest.

Closing Accounts You No Longer Need

Start by reviewing all your accounts. If an account charges maintenance fees and no longer serves a purpose, it’s time to close it. Fee-free accounts, however, may be worth keeping to maintain your credit history and provide a financial safety net if you return home someday.

Before deciding to keep any domestic account, check the bank’s policies on non-resident addresses. Some financial institutions may freeze or liquidate accounts once they learn you’re living abroad. As Pat Betley, a Financial Advisor at Creative Planning, warns:

"Many brokerage firms will freeze and eventually liquidate your accounts if they find out you’re living overseas".

If you expect payments from your home country – like tax refunds, Social Security, or rental income – or need to pay off remaining domestic bills, it might make sense to keep certain accounts open. For credit cards with annual fees, ask your bank about switching to a no-fee version. This way, you can keep the credit line without unnecessary costs.

It’s much easier to close accounts before you leave. Doing so remotely can be a hassle. Clear any outstanding balances, cancel unused direct debits at least a month in advance, and convert your accounts to electronic statements to avoid missing important updates. Even zero-balance accounts can cause trouble if they accumulate fees or hit FBAR reporting thresholds. Hui-Chin Chen, a CFP at Money Matters for Globetrotters, explains:

"What’s so bad about leaving an account with zero balance open? For one, you may incur account charges and technically owe the bank going forward".

By closing unnecessary accounts, you not only minimize fees but also simplify your future tax filings.

Opening Offshore Bank Accounts

Setting up offshore accounts can be a lengthy process, so it’s best to start early. Many international banks allow online applications, but you’ll need to meet their specific residency and eligibility requirements.

George Lee, Business Development Officer at Schwab Wealth Advisory, emphasizes the importance of starting early:

"I advise clients to get the ball rolling as early as possible, as there are several big items you’ll need to check off your list to help ensure a smooth transition".

Make sure your passport is valid for at least six months beyond your move date, as this is often required for visa and account applications. Additionally, most banks will ask for a local residential address – not a hotel or P.O. box – to complete the process.

Here’s a quick look at the typical documentation you’ll need:

| Typical Documentation Required | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Valid Passport (6+ months validity) | Primary identity verification |

| Visa or Work Permit | Proof of legal residency status |

| Proof of Local Address | Verification of physical residency (no P.O. boxes) |

| Proof of Income/Employment | Verification of source of funds |

| Proof of Support/Savings | Evidence of financial stability during your stay |

Offshore accounts often come with multi-currency options, which can help protect your purchasing power against currency swings. They also make transferring funds between your home-country and international accounts easier – sometimes even free.

However, opening offshore accounts doesn’t exempt you from U.S. reporting obligations. You’ll still need to comply with FBAR and FATCA requirements to avoid steep penalties. Consulting a cross-border tax expert or CPA can help you navigate these rules.

Once your offshore accounts are ready, you’ll have smoother financial access while living abroad.

Maintaining Access to Global Financial Services

A dual-banking strategy can make managing your finances much simpler. Keep one account in your home country for things like U.S. income or ongoing payments, and open another in your destination country for local expenses such as rent or utilities. This setup offers flexibility and simplifies currency management.

Notify your banks about your move and travel plans to prevent your accounts from being flagged for fraud during international transactions. Also, enable app-based two-factor authentication to avoid being locked out of your accounts while abroad.

If your bank doesn’t support international residents, consider using a trusted family member’s address or a mail forwarding service as your U.S. address. Before you leave, opening a multi-currency account, like the HSBC Global Money Account, can help you handle currency conversions and separate savings from daily expenses.

Unlock your phone before leaving so you can easily activate a local SIM card. Many countries require a local number to use banking apps. You may also need to register with local authorities (like the Anmeldung in Germany) to provide proof of residence for opening a local account.

Finally, steer clear of foreign mutual funds. Under U.S. tax law, these are classified as Passive Foreign Investment Companies (PFICs), which come with burdensome taxation and reporting requirements. By planning ahead, you can ensure smooth financial management no matter where you go.

Reviewing Your Investments, Retirement Accounts, and Insurance

Before moving abroad, it’s essential to review your investments, retirement accounts, and insurance policies. This step helps you avoid expensive mistakes and ensures your financial plans remain effective internationally.

Adjusting Your Investment Portfolio for International Living

Keep your main investment accounts in the U.S. Why? U.S. financial markets offer better liquidity, lower fees, and tax reporting tailored for the IRS. One common pitfall for expats is investing in foreign mutual funds or ETFs, which can trigger the Passive Foreign Investment Company (PFIC) rules. These rules can lead to tax rates as high as 60–70%.

Fidelity, Charles Schwab, and Vanguard are popular choices for expats. Another key tip: align your investment currency with your spending currency to reduce the risk of exchange rate fluctuations. For example, if you plan to retire in Europe, holding some euro-denominated assets may make sense. On the other hand, if your long-term expenses will be in U.S. dollars, it’s wise to keep your portfolio dollar-based.

When it comes to taxes, you’ll need to decide between the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) and the Foreign Tax Credit (FTC). The FTC is often better for those living in high-tax countries, as it provides a dollar-for-dollar credit against U.S. taxes. Interestingly, 62% of Americans filing taxes from abroad owe $0 in federal taxes after utilizing these credits.

Managing U.S. Retirement Accounts as an Expat

Your 401(k) and IRA accounts remain tax-deferred, but you’ll need an expat-friendly custodian to avoid issues like account freezes or forced liquidation. Managing these accounts effectively is critical as you adjust to your new international lifestyle.

If you want to keep contributing to an IRA while living abroad, you’ll need U.S.-taxable earned income. Keep in mind, income excluded under the FEIE doesn’t qualify. Using the Foreign Tax Credit instead can help, as it keeps your income “taxable” for U.S. purposes while still lowering your tax bill. For 2026, the IRA contribution limit is $7,500, with an additional $1,100 allowed for those aged 50 or older.

Understand how your destination country treats Roth IRAs. Some countries don’t honor their tax-free status and may tax distributions as regular income. If you’re a non-resident alien, filing Form W-8BEN with your plan administrator can help you claim tax treaty benefits and potentially reduce the default 30% withholding on distributions.

Lastly, formally break residency with your home state, especially if you’re moving from states like California, New York, or Virginia. These states may continue taxing your worldwide income and retirement distributions unless you establish a new domicile in a no-income-tax state like Florida or Texas.

Getting International Health Insurance Coverage

Health insurance is another essential piece of the puzzle when living abroad. Medicare generally doesn’t cover medical expenses outside the U.S., except in rare cases. However, it’s still important to enroll in Medicare Parts A and B when you turn 65. Skipping Part B can result in a permanent 10% premium increase for every 12 months you delay enrollment.

Charles Schwab emphasizes:

"Medicare generally won’t cover medical expenses incurred outside the U.S. That said, you should generally still sign up for Medicare and any Medicare supplements as soon as you’re eligible – typically at age 65 – or potentially face stiff penalties".

If you’re staying in one place, private local insurance typically costs $100 to $300 per month. For digital nomads or frequent travelers, international health plans that cover multiple countries (including the U.S.) are a better fit, ranging from $500 to $1,200 per month. During your initial months abroad, short-term travel health insurance can bridge the gap while you set up residency and local coverage.

Finally, be aware of local drug laws. Some medications that are legal in the U.S., like stimulants, opioids, or marijuana, may be prohibited or tightly regulated in other countries – even with a U.S. prescription. Digitizing your medical records and vaccination history and storing them securely in the cloud ensures quick access for healthcare providers abroad.

sbb-itb-39d39a6

Using Asset Protection Structures

Once you’ve streamlined your financial accounts and investments, the next step is safeguarding your wealth from potential risks. High-net-worth individuals (those with assets exceeding $1 million) often use legal structures to protect their assets from creditors, lawsuits, and political instability.

Forming Offshore Companies

Creating an offshore company – typically an LLC or corporation – places your assets under the legal framework of a foreign jurisdiction. This setup makes it significantly harder for creditors to access your wealth, as they would need to file expensive lawsuits in a foreign court. Some jurisdictions, like Nevis and the Cook Islands, don’t recognize U.S. court rulings, forcing claimants to restart the litigation process from scratch.

That said, holding U.S. real estate in an offshore structure is not recommended. Since U.S. courts maintain jurisdiction over physical property within the country, such arrangements offer little protection. Offshore entities are better suited for liquid assets like cash or securities.

Keep in mind that setting up an offshore company doesn’t exempt you from U.S. tax obligations. You’re still required to report foreign accounts (via FBAR) and file IRS forms like 3520 and 3520-A. Initial setup costs range from $8,000 to $15,000, with annual maintenance fees typically between $2,000 and $5,000.

If you’re considering this route, start by understanding how offshore companies can protect your liquid assets.

Using Offshore Trusts and Foundations

Offshore trusts offer an even higher level of asset protection. By transferring assets into an irrevocable trust, legal ownership is shifted to the trustee, adding a robust layer of security.

Jurisdictions like Nevis and the Cook Islands are particularly attractive for these trusts due to their strict legal protections. For example, in Nevis, a creditor must prove fraud "beyond a reasonable doubt" (a 90%+ probability) to challenge a trust transfer, compared to the much lower "preponderance of evidence" standard (just over 50%) used in U.S. civil cases. Additionally, Nevis imposes a short 2-year statute of limitations for such challenges, compared to the typical 4 years in most U.S. states. Creditors are also required to post a $25,000 bond before filing a lawsuit, adding another hurdle.

| Feature | U.S. Domestic Trust | Offshore Trust (Nevis/Cook Islands) |

|---|---|---|

| Judgment Recognition | Must recognize sister-state judgments | Generally does not recognize U.S. judgments |

| Burden of Proof | Preponderance of evidence (>50%) | Beyond a reasonable doubt (~90%) |

| Statute of Limitations | Typically 4 years | Often 2 years |

| Creditor Requirements | Minimal | May require $25,000+ bond to sue |

Offshore trusts also offer estate planning advantages, allowing you to pass on wealth to future generations without going through the public probate process. However, for U.S. tax purposes, most offshore trusts are classified as "foreign grantor trusts", meaning you’ll still be taxed on trust income as if you earned it yourself. Note that the U.S. federal estate tax exemption for 2025 is $13.99 million per individual.

Foundations, which operate under civil law rather than common law, provide another option. Unlike trusts, foundations have their own legal personality, functioning more like a company. This structure can be advantageous in jurisdictions such as Switzerland or Panama.

To avoid potential issues like fraudulent transfer claims and to ensure compliance with U.S. tax laws, consult a cross-border tax professional. By incorporating these asset protection strategies, you can add another layer of security to your financial plan while preparing for life abroad.

Planning for Exit Tax if Renouncing U.S. Citizenship

If you’re thinking about renouncing your U.S. citizenship or giving up your green card, it’s crucial to understand the exit tax. This tax applies to your worldwide assets, treating them as if they were sold at fair market value the day before you renounce citizenship or terminate long-term residency. The financial impact can be significant, so careful planning is key.

What is the Exit Tax?

The U.S. exit tax operates on the assumption that all your worldwide assets are sold at their fair market value the day before expatriation. As Mike Wallace, CEO of Greenback Expat Tax Services, puts it:

"The IRS acts as if you sold all your property (houses, stocks, businesses) the day before you renounce citizenship".

However, not everyone is subject to this tax. You are classified as a "covered expatriate" – and therefore liable for the exit tax – if you meet any of these three criteria:

- Net Worth Test: Your net worth is $2,000,000 or more on the expatriation date.

- Tax Liability Test: Your average annual net income tax over the past five years exceeds $211,000 (for 2026).

- Compliance Test: You fail to certify on Form 8854 that you’ve met all U.S. federal tax obligations for the previous five years.

Long-term green card holders also face these criteria. Interestingly, only about 1 in 15 individuals who renounce their U.S. citizenship actually meet the financial thresholds to owe this tax.

For 2026, the statutory exclusion amount for unrealized gains is $910,000. This means that gains below this threshold are not taxed under the exit tax rules. However, certain assets are treated differently. For example, IRAs and HSAs are taxed as "deemed distributions", meaning the entire balance is treated as ordinary income without the benefit of the exclusion. On the other hand, 401(k)s and pensions can often defer taxation, with a 30% withholding tax applied to future distributions if you submit Form W-8CE within 30 days of expatriation.

| Asset Type | Tax Treatment for Covered Expatriates | Exclusion Applicable? |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Assets (Stocks, Real Estate) | Mark-to-market (deemed sale at FMV) | Yes ($910,000 in 2026) |

| Specified Tax-Deferred (IRA, HSA) | Deemed distribution (entire balance taxed) | No |

| Eligible Deferred Comp (401(k)) | 30% withholding at time of future distribution | No |

Beyond the exit tax itself, there are additional financial concerns. For instance, U.S. heirs of a covered expatriate may face a 40% inheritance tax on gifts or bequests exceeding the annual exclusion ($19,000 for 2026). The State Department also charges a $2,350 renunciation fee, and failing to file Form 8854 can result in a $10,000 penalty.

Now, let’s look at ways to reduce your exposure to the exit tax before taking the step to expatriate.

How to Reduce Exit Tax Liability

Reducing exit tax liability requires thoughtful financial planning well ahead of your renunciation date. If your net worth is approaching $2,000,000, consider gifting assets to a spouse or heirs to bring your net worth below the covered expatriate threshold. For 2026, you can gift up to $195,000 tax-free to a non-citizen spouse. Start this process 6–18 months before your renunciation appointment to allow time for proper valuations and transfers.

Timing matters too. If you’re a green card holder, expatriating before your 8th year of residency can help you avoid long-term classification and the exit tax. Selling underperforming assets to offset gains is another way to lower your total taxable unrealized gains.

Ensure you’re fully compliant with U.S. tax laws before renouncing. The IRS Streamlined Procedures can help you correct past filing errors, as non-compliance automatically triggers covered expatriate status regardless of your financial situation. If you have a 401(k), file Form W-8CE with your plan administrator within 30 days of expatriation to avoid having the account treated as a fully taxable lump-sum distribution.

Renouncing your citizenship doesn’t automatically end state tax residency. Be sure to cancel your driver’s license and voter registration in states like California or New York to avoid ongoing state taxation on your global income.

Conclusion

Relocating from the U.S. requires thorough financial planning to avoid unnecessary stress and complications. The steps you take before leaving can make the difference between a seamless transition and a host of financial headaches.

For instance, failing to file an FBAR can lead to hefty fines, and investing in foreign mutual funds without proper guidance might result in punitive PFIC taxation and complex reporting requirements. Additionally, some Americans are caught off guard when their U.S. brokerage accounts are frozen or liquidated after a foreign address is detected. On top of that, your home state could continue taxing your worldwide income, even after you’ve moved abroad.

On the bright side, many expats successfully minimize their tax obligations by leveraging exclusions and credits. Experts often recommend assembling a team of cross-border professionals – such as a CPA, international estate attorney, and financial advisor – to ensure a smooth transition. While professional expat tax preparation typically costs between $530 and $700 annually, this expense is relatively minor compared to the potential penalties and challenges of non-compliance.

FAQs

What financial steps should I take before moving abroad?

Relocating internationally? There are a few financial steps you’ll want to handle upfront to make the transition as smooth as possible.

Start by informing your banks, investment firms, and any other financial institutions about your move. This ensures they can continue providing services while you’re living abroad. Keep in mind that some accounts might face restrictions or even closure if your address changes to a non-U.S. location. Confirming accessibility ahead of time is a smart move.

Next, get familiar with your tax responsibilities. Even while living overseas, U.S. citizens often have ongoing filing requirements. You’ll also want to check whether exit taxes or other obligations might apply. Planning for currency exchanges and securing international health insurance are other critical steps. And, of course, make sure your passport and travel documents are current.

Timing your move carefully can also work to your advantage, especially when it comes to tax residency rules. A well-timed relocation can help you avoid unexpected tax surprises. By taking these steps in advance, you’ll protect your finances and stay on top of compliance while embracing your new international adventure.

What steps can U.S. citizens take to avoid tax penalties while living abroad?

To steer clear of tax penalties as a U.S. citizen living abroad, it’s essential to stay on top of your tax responsibilities. Even if all your income is earned overseas, you’re still required to file an annual tax return with the IRS. The good news? You may be eligible for tax breaks like the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion (FEIE) or the Foreign Tax Credit, which can significantly lower your U.S. tax bill.

Another key obligation is reporting foreign accounts. If the total value of your foreign accounts exceeds specific thresholds, you’ll need to file the FBAR (Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts). Keeping thorough records and working with a tax professional who specializes in expatriate taxes can make a big difference in staying compliant and avoiding hefty penalties.

What do I need to know about reporting and managing foreign bank accounts?

If you’re a U.S. person with foreign bank accounts, it’s crucial to know your reporting responsibilities. An FBAR (Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts) is required if the combined value of your foreign accounts exceeds $10,000 at any point during the calendar year. This report must be submitted electronically through FinCEN by April 15, though extensions may be available.

Beyond the FBAR, U.S. taxpayers must also disclose foreign accounts on their federal tax returns, often on Schedule B of Form 1040. Under FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act), individuals with substantial foreign financial assets may need to file additional forms. Non-compliance can result in hefty penalties, so working with a tax professional is strongly advised to ensure all obligations are met.