Offshore investments can be a smart way to diversify your portfolio, but staying compliant with U.S. tax laws is non-negotiable. Here’s what you need to know:

- Reporting is mandatory: U.S. taxpayers must report worldwide income and foreign assets, including offshore accounts, using forms like FBAR (FinCEN Form 114) and FATCA (Form 8938).

- Noncompliance is costly: Penalties for failing to report can range from $10,000 for non-willful violations to 50% of account balances for willful violations.

- Key regulations: FATCA, FBAR, PFIC rules, and CFC rules govern offshore investments and require meticulous reporting.

- Tools for compliance: Use IRS resources, specialized advisors, and voluntary disclosure programs to address past errors and ensure future compliance.

- Choose jurisdictions wisely: Consider tax treaties, economic substance rules, and local legal systems when setting up offshore accounts or structures.

The key takeaway? Proper disclosure and adherence to U.S. tax laws are essential to avoid penalties and safeguard your investments. Offshore investing is legal, but it’s your responsibility to follow the rules.

Key U.S. Regulations for Offshore Investments

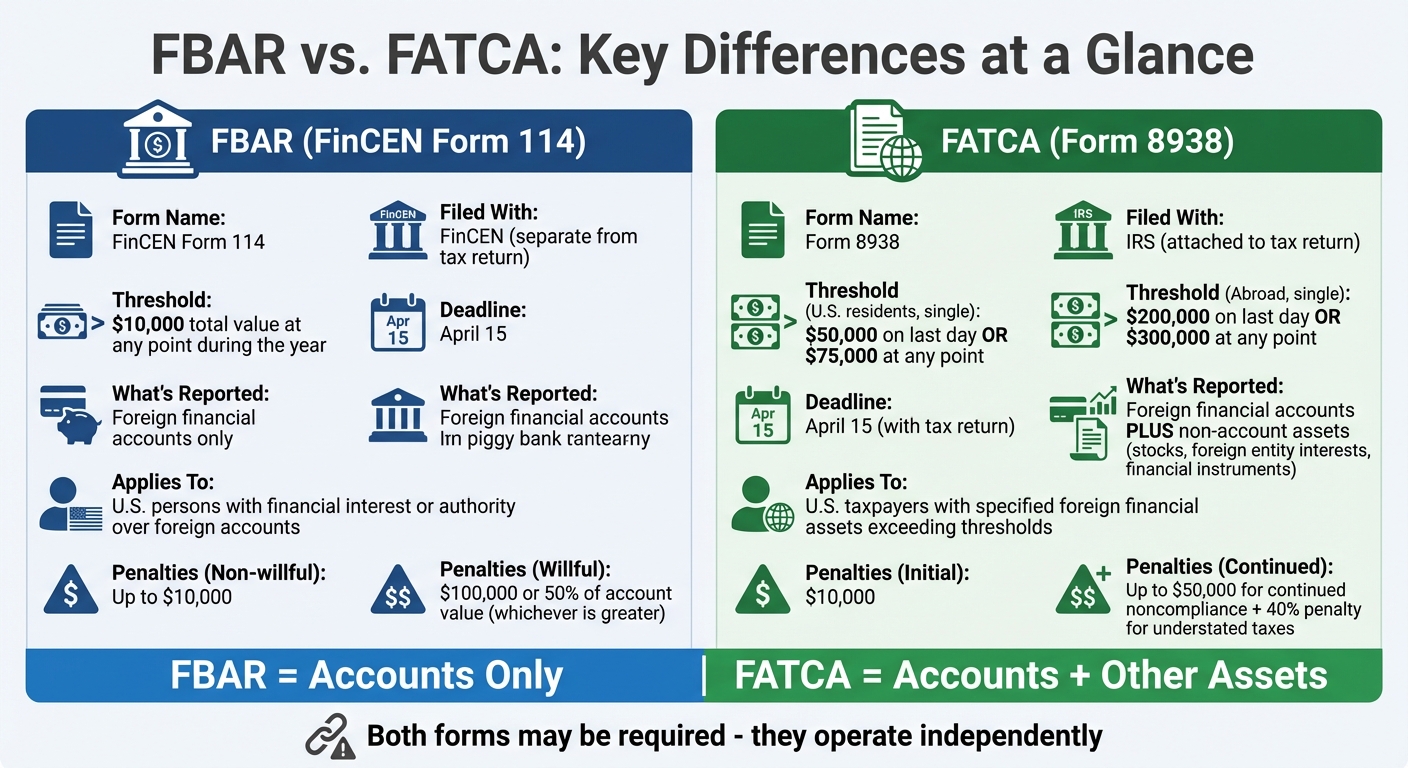

FBAR vs FATCA Reporting Requirements Comparison Chart

Navigating offshore investments means understanding the specific U.S. regulations that govern them. These rules come with thresholds, deadlines, and reporting requirements that investors need to follow carefully.

FATCA and FBAR Requirements

When it comes to reporting foreign accounts, two key requirements come into play: FBAR (FinCEN Form 114) and FATCA (Form 8938). While they share some similarities, they operate independently and have distinct rules.

FBAR applies to U.S. persons with a financial interest in or authority over foreign accounts if the total value exceeds $10,000 at any point during the calendar year. This form is filed directly with FinCEN and not alongside your tax return. The deadline for FBAR is April 15 of the following year.

FATCA, on the other hand, requires U.S. taxpayers to report specified foreign financial assets if they exceed certain thresholds. For single filers residing in the U.S., the threshold is $50,000 on the last day of the tax year or $75,000 at any point during the year. For those living abroad, the thresholds are higher, starting at $200,000 for single filers. Form 8938 is attached to your annual tax return, also due by April 15.

The key difference? While FBAR focuses solely on foreign financial accounts, FATCA extends to non-account assets like foreign stocks, interests in foreign entities, and financial instruments with non-U.S. persons. To convert foreign currency amounts to U.S. dollars, use the U.S. Treasury Bureau of the Fiscal Service‘s exchange rates from the last day of the tax year.

Failing to file Form 8938 can lead to penalties starting at $10,000, with additional fines reaching up to $50,000 for continued noncompliance. There’s also a 40% penalty for understated taxes. Plus, the statute of limitations extends to three years after the information is provided – or six years if more than $5,000 in gross income is omitted due to foreign assets.

PFIC Rules and Reporting Obligations

A Passive Foreign Investment Company (PFIC) is any foreign corporation that meets either of these criteria:

- Income Test: At least 75% of its gross income is passive (e.g., dividends, interest).

- Asset Test: At least 50% of its assets generate passive income.

This category often includes foreign mutual funds, ETFs, hedge funds, and offshore trusts.

By default, PFICs are taxed under the Excess Distribution regime, where capital gains from selling PFIC shares are treated as ordinary income. On top of that, deferred taxes come with interest charges. An "excess distribution" refers to any distribution exceeding 125% of the average distributions from the past three years.

"If a taxpayer does not make any election for their PFICs, then they will be taxed under the excess distribution regime… This may result in a tax liability of more than 50%."

– Golding & Golding, International Tax Law Firm

To comply, investors must file IRS Form 8621 annually for each PFIC held, even if there are no distributions. However, those with PFIC holdings valued at $25,000 or less ($50,000 for married filing jointly) are exempt, provided no excess distributions occurred. Failing to file Form 8621 leaves the entire tax return open for audit indefinitely.

There are two elections that can ease the tax burden:

- Qualified Electing Fund (QEF) Election: Taxes a pro-rata share of earnings, preserving capital gains treatment. However, it requires an annual information statement from the foreign fund.

- Mark-to-Market (MTM) Election: Available for publicly traded PFICs, this allows gains to be recognized annually as ordinary income, avoiding the interest charges of the default regime.

Keep in mind, under the "Once a PFIC, always a PFIC" rule, once a corporation is designated as a PFIC, it retains that status unless a specific purging election is made.

Controlled Foreign Corporation Rules and GILTI Tax

For foreign corporations, U.S. regulations also include rules for controlled ownership and income taxation. A Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) is any foreign corporation where U.S. shareholders own more than 50% of the voting power or stock value during the tax year. A "U.S. shareholder" is defined as any U.S. person owning at least 10% of the voting power or value, either directly, indirectly, or constructively.

When CFC rules are triggered, U.S. shareholders must include their share of the corporation’s undistributed earnings as current income. This includes:

- Subpart F income: Passive income such as dividends, interest, rents, and royalties.

- Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI): Income exceeding a 10% return on the CFC’s tangible assets.

- Investments in U.S. property under Section 956.

"Subpart F income is designed to prevent US taxpayers from sheltering passive or mobile income in foreign corporations."

– Bradley Albin, International Corporate Tax Director, USTAXFS

Subpart F income is taxed at ordinary income rates, but under the "de minimis" rule, it can be excluded if it’s less than 5% of gross income or $1,000,000, whichever is lower.

For GILTI, individual shareholders can elect under Section 962 to be taxed as a corporation, benefiting from corporate tax rates and foreign tax credits. To comply with CFC rules, investors must report their interests using Form 5471.

These regulations are complex, but understanding them is crucial for staying compliant and avoiding hefty penalties. Offshore investments require careful attention to detail and proactive reporting.

sbb-itb-39d39a6

How to Stay Legally Compliant with Offshore Investments

Staying compliant with offshore investment regulations requires more than just understanding the rules – it demands consistent action and robust systems to ensure you meet legal requirements year after year.

Working with Specialized Legal and Tax Advisors

Navigating offshore compliance is complicated, which is why working with specialized legal and tax advisors is essential. These professionals can assess any past noncompliance and guide you through the appropriate procedures. For example, if your noncompliance was unintentional, you might qualify for the Streamlined Filing Compliance Procedures, which typically impose a 5% penalty on the highest year-end value of your foreign assets. On the other hand, willful noncompliance may require using the IRS Criminal Investigation Voluntary Disclosure Practice to address liabilities and avoid criminal charges.

"A single email, a conversation with a CPA, or a financial advisor’s warning can shift a case from ‘non-willful’ into ‘high risk.’"

– Todd Unger, Tax Attorney

Advisors can also help identify the forms you need to file, such as FBAR (FinCEN Form 114), FATCA (Form 8938), Form 3520 for foreign trusts and gifts, or Form 5471 for foreign corporations. They assist in gathering financial records, calculating penalties, and drafting "Reasonable Cause" statements to dispute or eliminate penalties. For willful cases, legal counsel can outline a resolution strategy and provide protection from criminal prosecution. Timing is critical – once the IRS starts an audit, eligibility for lenient amnesty programs ends, so acting early is key.

Using Compliance Tools and Resources

The IRS and FinCEN offer various tools to help taxpayers meet compliance requirements. For instance, the BSA E-Filing System is the mandatory platform for electronically filing FBAR (Form 114). Additionally, the IRS provides online accounts for individuals, businesses, and tax professionals, allowing users to access tax records, monitor payments, and view notifications.

Other helpful resources include the IRS’s dedicated pages for Streamlined Filing Compliance Procedures and foreign trust reporting. The Internal Revenue Manual (IRM) 4.63.3 is a valuable reference for understanding complex issues like PFIC rules and foreign trust obligations. The IRS also offers specialized hotlines for its Voluntary Disclosure Practice and a secure Document Upload Tool for responding to offshore-related notices.

Fixing and Preventing Noncompliance

If you’ve missed filings, voluntary disclosure programs can help you address past errors. For U.S. residents whose noncompliance was non-willful – caused by negligence, mistakes, or a good-faith misunderstanding of the law – the Streamlined Domestic Offshore Procedures (SDOP) may apply. Similarly, U.S. taxpayers living abroad who meet specific residency requirements might qualify for the Streamlined Foreign Offshore Procedures, which can waive penalties entirely.

"Non-willful conduct is conduct that is due to negligence, inadvertence, or mistake or conduct that is the result of a good faith misunderstanding of the requirements of the law."

– Internal Revenue Service

Penalties for noncompliance can be steep. Non-willful FBAR violations can result in fines of up to $10,000 per year, while willful offenses can incur penalties of $100,000 or 50% of the maximum account value, whichever is greater. Once you’ve completed a disclosure procedure, staying compliant in subsequent years is just as important. Keep in mind, you’ll need a valid Taxpayer Identification Number (SSN or ITIN) before submitting any streamlined procedure application, as submissions without one won’t be processed.

Setting Up Offshore Structures While Staying Compliant

Choosing the Right Offshore Jurisdiction

When setting up offshore structures, picking the right jurisdiction is critical. Look for locations that offer favorable tax benefits, regulatory reliability, and straightforward access. Start by checking whether the jurisdiction is on the EU blacklist or the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) grey list. Being associated with a blacklisted country can lead to denied tax deductions, higher withholding rates, and challenges when opening bank accounts.

Tax treaty networks play a key role. For example, Cyprus has over 60 Double Tax Treaties, and Malta boasts 70+, both of which can help reduce withholding taxes. Meanwhile, Hong Kong operates on a territorial tax system with rates of 8.25% on the first HKD 2 million of profit and 16.5% thereafter. Cyprus stands out with a corporate tax rate of 12.5% and a 0% tax on non-resident dividends.

"The international reputation is not a matter of perception, but much more importantly, it is a matter of how willing other professionals and financial service providers will be to deal with entities formed in that jurisdiction." – Afridi & Angell

Another factor to consider is economic substance requirements. Jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Cayman Islands, and Bermuda now require businesses to show actual economic activity – such as hiring local staff or maintaining offices – to align with OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) standards. This means you’ll need a physical office to store corporate documents and accounts. The legal system also matters: Common Law jurisdictions (e.g., BVI and Cayman Islands) tend to offer more flexibility for trust structures, while Civil Law jurisdictions (e.g., Switzerland) may have "forced heirship" rules that could conflict with trust provisions.

Before incorporating, confirm that international banks and payment providers will work with entities from your chosen jurisdiction. Also, factor in costs: incorporation fees can range from $200 to $2,000, while annual maintenance costs can run anywhere from $1,000 to over $10,000. Once you’ve chosen your jurisdiction, focus on structures that balance asset protection with compliance.

Forming Offshore Companies and Trusts

After selecting a jurisdiction, choose an offshore structure that suits your goals. International Business Companies (IBCs) are ideal for fundraising and financing, while Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) provide operational flexibility with fewer requirements. For estate planning and asset protection, trusts or foundations can help avoid probate and forced heirship issues while safeguarding family business interests.

U.S. persons face specific reporting obligations when managing foreign trusts or companies. For instance, if you transfer assets to a foreign trust and retain control or benefit, you’ll typically be taxed on the trust’s income under grantor trust rules. The trust must file Form 3520-A annually, and you’ll need to file Form 3520 to report transactions with the trust. For those controlling a foreign corporation, Form 5471 is required. Additionally, an Employer Identification Number (EIN) must be obtained for the trust, rather than using a personal SSN or ITIN.

"Optimised HoldCo tax structures may only be effective if there is sufficient economic and commercial substance that is transparent to tax authorities." – Sovereign Group

Work closely with both U.S. tax advisors and local attorneys in your chosen jurisdiction to address potential legal conflicts. For example, if you’re setting up a trust in a Civil Law jurisdiction like Switzerland, ensure you understand how local courts handle trust provisions and forced heirship rules. Thorough documentation is essential – board minutes, management resolutions, and other records should clearly demonstrate the business purpose of your offshore structure beyond tax avoidance.

For high-net-worth individuals considering expatriation, be mindful of the "exit tax." This applies if your net worth exceeds $2 million or if your average annual income tax for the past five years surpasses $206,000 (for 2025). The 2025 exit tax gain exclusion is $890,000, and expatriates lose the lifetime gift and estate tax exclusion of $13.9 million, which drops to just $60,000 for non-U.S. persons.

Conclusion

Offshore investments are entirely legal as long as they comply with applicable laws, and proper disclosure is key to safeguarding both your wealth and reputation. As Brinen & Associates aptly states:

"Understanding the landscape of offshore finance – and where legal tax planning ends and tax evasion begins – is critical to safeguarding both your wealth and your reputation".

Failing to comply with these regulations can result in harsh financial penalties and significant reputational harm. Beyond monetary fines, violations may lead to asset seizures, criminal prosecution, and long-term damage to your standing. To date, the IRS has collected over $6.5 billion from 45,000 participants through its Offshore Voluntary Disclosure efforts.

To mitigate these risks, it’s crucial to follow all reporting requirements diligently. This includes filing FBAR, Form 8938, Form 3520, and Form 8621 as needed. Remember, U.S. taxpayers owe taxes on their worldwide income, whether or not that income is repatriated.

For those with past errors, addressing them through formal IRS disclosure programs – not quiet filings – is the safest route. Consulting with board-certified international tax law specialists can help you navigate complex issues like PFIC and GILTI. Additionally, when opening foreign accounts, always disclose your U.S. citizenship to avoid fraud allegations.

Ultimately, transparency and strict compliance with legal standards form the foundation of effective offshore asset protection. Offshore structures are most effective when they are fully documented, transparent, and compliant with all applicable laws.

FAQs

What are the consequences of not reporting offshore investments properly?

Failing to meet offshore investment reporting requirements can result in hefty penalties. Civil fines can climb as high as $10,000 for not disclosing offshore accounts, while willful violations may lead to criminal charges or fines that could surpass the account’s entire value.

To steer clear of these risks, it’s crucial to fully understand and adhere to all reporting rules, including filing precise details under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) and the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). Seeking guidance from a qualified legal advisor or leveraging compliance tools can help you stay on track and safeguard your investments.

What’s the difference between FATCA and FBAR when reporting offshore accounts?

FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act) and FBAR (Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts Report) share a common goal: keeping offshore tax evasion in check. However, they differ in scope and requirements.

FATCA requires U.S. taxpayers to report certain foreign financial assets by filing Form 8938 along with their annual tax return. It also places obligations on foreign financial institutions (FFIs) to disclose accounts held by U.S. persons.

Meanwhile, FBAR focuses specifically on foreign bank accounts. U.S. persons must electronically file FinCEN Form 114 if the total balance across all foreign accounts exceeds $10,000 at any point during the year. Unlike FATCA, FBAR zeroes in on account balances rather than the types of assets held.

While both regulations aim to curb tax evasion, they differ in thresholds, filing processes, and what they require you to report. Knowing these differences is crucial to avoid penalties and stay on the right side of compliance.

What are the tax consequences of owning Passive Foreign Investment Companies (PFICs)?

Owning Passive Foreign Investment Companies (PFICs) comes with hefty U.S. tax responsibilities. The IRS enforces a strict taxation framework that often results in higher tax rates on gains, along with interest charges on any deferred taxes. If you’re a U.S. taxpayer with PFIC holdings, you’re required to file IRS Form 8621 to report both your investments and any income generated from them.

To steer clear of penalties or compliance headaches, it’s essential to fully understand these reporting obligations. Working with a tax advisor who specializes in international investments can make a big difference. By staying ahead of these requirements, you can better manage your tax duties and safeguard your financial interests.