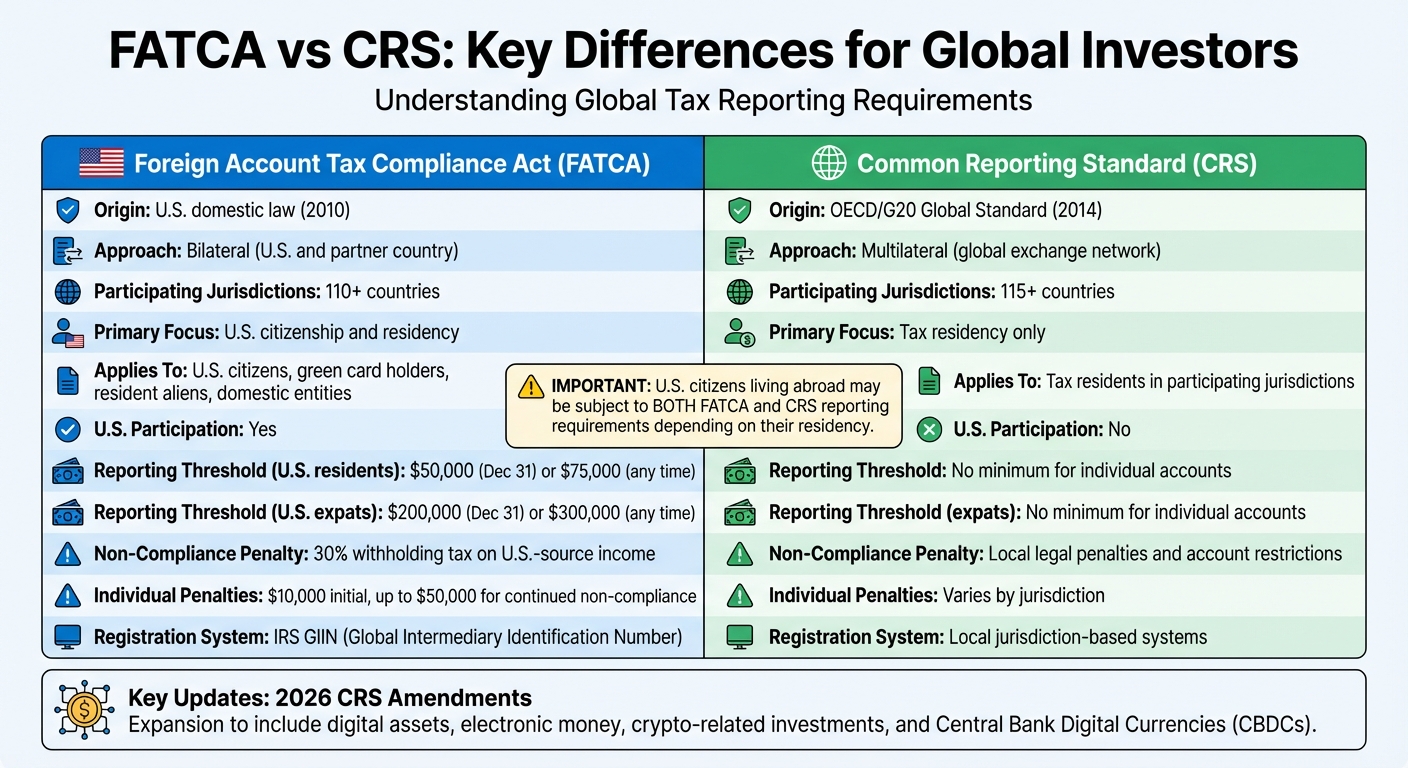

When managing offshore investments, two key regulations – FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act) and CRS (Common Reporting Standard) – govern how financial data is shared internationally. Here’s what you need to know:

- FATCA: A U.S. law targeting tax evasion by requiring foreign financial institutions (FFIs) to report U.S. account holders to the IRS. Non-compliance can lead to a 30% withholding tax on U.S.-sourced income.

- CRS: A global initiative by the OECD for automatic exchange of financial information among 115+ countries. It focuses on tax residency rather than citizenship.

- Key Differences:

- FATCA applies to U.S. citizens, green card holders, and entities, while CRS applies to tax residents in participating jurisdictions.

- The U.S. participates in FATCA but not CRS.

- Penalties: Non-compliance can result in fines up to $50,000 for individuals and withholding taxes or legal penalties for institutions.

- 2026 CRS Updates: CRS will expand to include digital assets like electronic money and crypto-related investments.

Both frameworks demand transparency, making compliance critical to avoid penalties. Whether you’re a U.S. taxpayer or an international investor, understanding these rules is essential to protect your assets.

What is FATCA?

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) is a U.S. federal law introduced in 2010 as part of the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment (HIRE) Act. Its main goal is to prevent tax evasion by U.S. taxpayers who hold investments in foreign accounts and financial assets. Before FATCA, many U.S. taxpayers failed to report offshore accounts to the IRS. FATCA changed that by requiring foreign financial institutions (FFIs) to report account information for U.S. persons directly to the IRS.

FATCA creates a dual reporting system: FFIs must report details about U.S. account holders, and U.S. persons must disclose their foreign financial accounts if they exceed specific thresholds. This dual system acts as a safeguard, making it harder for individuals to hide assets.

FATCA’s Scope and Objectives

FATCA operates on a global level. It applies to U.S. persons, which includes U.S. citizens (even those residing abroad), resident aliens, and domestic entities like partnerships, corporations, and trusts. This broad definition ensures that all U.S. persons, including expatriates and green card holders, are covered.

To enforce compliance, FATCA imposes a 30% withholding tax on U.S.-source payments made to non-compliant FFIs. This penalty encourages most institutions to register and comply. Over 110 jurisdictions have agreed to participate in FATCA, creating an extensive information-sharing network.

Countries typically comply with FATCA through Intergovernmental Agreements (IGAs), which come in two forms. Under a Model 1 IGA, FFIs send U.S. account holder information to their local tax authority, which then forwards it to the IRS. In contrast, under a Model 2 IGA, FFIs report directly to the IRS. These IGAs help foreign governments address privacy laws that might otherwise conflict with FATCA’s requirements. FFIs must also register with the IRS and obtain a Global Intermediary Identification Number (GIIN) to confirm compliance.

Key Terms and Definitions

Here’s a quick guide to some essential FATCA terms and their roles:

| Term | Definition | Reporting Obligation |

|---|---|---|

| FFI | Foreign Financial Institution (e.g., banks, custodians, brokers, hedge funds, private equity funds, certain insurance companies) | Must report U.S. account holders to the IRS or local tax authority. |

| NFFE | Non-Financial Foreign Entity (a non-U.S. entity that isn’t a financial institution) | Must disclose substantial U.S. owners to withholding agents. |

| U.S. Person | U.S. citizen, resident, or entity | Must report foreign assets exceeding $50,000 on Form 8938. |

| GIIN | Global Intermediary Identification Number | Used by FFIs to confirm FATCA compliance. |

| IGA | Intergovernmental Agreement | Framework for sharing tax data across borders. |

| IDES | International Data Exchange Service | A secure system for transmitting FATCA data to the U.S. |

sbb-itb-39d39a6

What is CRS?

The Common Reporting Standard (CRS) is a global initiative developed by the OECD to combat offshore tax evasion. It requires the automatic exchange of financial account information between participating countries. Unlike FATCA, which focuses on U.S. citizens, CRS establishes a multilateral framework where countries share data about financial accounts. The OECD Council approved this standard in July 2014, following a G20 request.

"The Standard calls on jurisdictions to obtain information from their financial institutions and automatically exchange that information with other jurisdictions on an annual basis." – OECD

Under CRS, financial institutions must determine their account holders’ tax residency and report this information to their local tax authorities. These authorities then share the data with the account holder’s home country. By 2025, over 100 jurisdictions are expected to participate in this system. In August 2022, the OECD introduced updates to include electronic money products and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), reflecting the evolving financial landscape.

CRS Purpose and Scope

CRS is designed to close gaps that allowed individuals to hide assets in foreign accounts. It applies broadly to financial institutions, account types, and taxpayers to ensure compliance. Unlike FATCA, which is based on citizenship, CRS focuses on tax residency. For example, a French tax resident living in Switzerland would have their account information reported by Swiss banks to French tax authorities, regardless of their nationality.

The framework operates through bilateral or multilateral agreements among participating countries. Each country enacts domestic laws requiring financial institutions to identify "Reportable Persons" – those considered tax residents in partner jurisdictions – and to submit annual reports. Recent updates have tightened due diligence processes, removed potential loopholes, and limited exemptions to legitimate non-profit organizations. By centering on tax residency, CRS introduces clear distinctions from FATCA.

How CRS Differs from FATCA

Although both CRS and FATCA aim to enhance financial transparency, their approaches differ significantly. FATCA is a U.S. law enforced through bilateral agreements, while CRS is a global standard enabling multilateral data exchanges. FATCA focuses on U.S. citizenship and residency, while CRS relies solely on tax residency. Notably, the United States does not participate in CRS as a reporting jurisdiction. This means U.S. financial institutions do not share information about foreign account holders under CRS but must comply with FATCA requirements for U.S. citizens.

| Feature | FATCA | CRS |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | U.S. domestic law | OECD / G20 Global Standard |

| Approach | Bilateral (U.S. and partner country) | Multilateral (global exchange network) |

| Primary Focus | U.S. citizenship and residency | Tax residency |

| U.S. Participation | Yes | No |

| Non-compliance Risk | 30% withholding on U.S. source income | Local legal penalties and account restrictions |

This dual compliance system creates unique challenges for global investors. U.S. citizens living abroad are subject to FATCA due to their citizenship and may also face CRS reporting based on their tax residency in another country. Meanwhile, non-U.S. investors are impacted by CRS if they are tax residents in participating jurisdictions but only need to comply with FATCA if they have U.S. investments or tax obligations.

Compliance Requirements for FATCA and CRS

Meeting the compliance standards for FATCA and CRS involves a clear understanding of classification, registration, and due diligence protocols. The requirements differ depending on whether an institution is navigating FATCA’s U.S.-centric framework or CRS’s multilateral approach. Below, we’ll break down the steps financial institutions must take to stay compliant.

Entity Classification and Registration

The first step for financial institutions is determining their classification status. Both FATCA and CRS classify Reporting Financial Institutions (RFIs) into categories such as depository institutions (e.g., banks), custodial institutions (e.g., mutual funds), investment entities (e.g., hedge funds and private equity firms), and insurance companies offering cash value products. Certain entities, however, are exempt from reporting, including most government entities, non-profits, small local financial institutions, and specific retirement entities.

Under FATCA, Foreign Financial Institutions (FFIs) must register through the IRS website to obtain a Global Intermediary Identification Number (GIIN). This number confirms compliance to both withholding agents and the IRS. The registration process is entirely online, and the IRS publishes a monthly list of registered FFIs along with their GIINs. This allows institutions to avoid the 30% withholding tax on U.S.-source payments. On the other hand, CRS relies on local jurisdiction-based registration systems rather than a centralized global platform.

Customer Due Diligence and Reporting

After classification and registration, financial institutions must implement due diligence procedures to identify accounts subject to reporting. This involves determining whether account holders meet the criteria for FATCA or CRS reporting. Institutions typically collect self-certifications – such as Forms W-8 or W-9 under FATCA – and supporting documents to verify the information provided.

The due diligence process demands thorough reviews of documentation. For entity accounts, institutions must identify foreign entities with substantial U.S. owners under FATCA or establish tax residency under CRS rules. Data is then transmitted securely via the International Data Exchange Service (IDES), which facilitates communication between financial institutions, tax authorities, and the U.S.. Maintaining compliance requires institutions to stay updated on regulatory changes, as standards continue to evolve. These procedures lay the groundwork for the adjustments coming with the 2026 CRS amendments.

2026 CRS Amendments

Starting in January 2026, CRS will undergo major updates to include modern financial instruments. Following a detailed review, the OECD released a 128-page consolidated text outlining these changes. The revisions expand reporting requirements to cover electronic money products and Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), ensuring digital financial tools are treated like traditional accounts.

"Further revisions have been made to ensure that indirect investments in crypto-assets, through derivatives and investment vehicles, are now subject to the CRS." – OECD

Investment entities managing crypto-asset derivatives and related vehicles will face expanded definitions and stricter due diligence requirements. The amendments also simplify compliance for legitimate non-profit organizations by introducing a carve-out for genuine charitable entities. These updates reflect the shifting dynamics of global finance, requiring institutions to reassess their classification systems and review digital holdings that may now fall under reporting obligations. To ensure compliance, the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes has increased monitoring efforts, releasing jurisdiction-specific review reports in January 2026 for countries like Antigua and Barbuda and Seychelles.

Reporting Obligations and Penalties

Annual Reporting Requirements

Both FATCA and CRS follow a calendar year framework, with account balances typically assessed as of December 31. Financial institutions must gather detailed information for each reportable account, including the account holder’s details, year-end balances, gross interest, dividends, other income earned throughout the year, and gross proceeds from the sale or redemption of financial assets.

Submission deadlines differ across jurisdictions. In Australia, for instance, financial institutions must submit their reports to the ATO by July 31 each year. These submissions are made using standardized formats. Under FATCA, U.S. TINs are mandatory, while CRS requires institutions to make reasonable efforts to obtain foreign TINs and dates of birth for pre-existing accounts. Some jurisdictions offer a 90-day grace period to collect missing TINs before accounts are restricted or closed.

One notable difference between FATCA and CRS is how they handle account closures. CRS only requires institutions to report the fact that an account was closed during the year. In contrast, FATCA mandates reporting the account balance immediately before closure. Additionally, filing a "nil report" when no reportable accounts exist helps reduce inquiries from tax authorities.

Staying compliant with these requirements is crucial to avoiding steep financial penalties.

Penalties for Non-Compliance

Failing to meet these reporting obligations can lead to severe financial and procedural repercussions. U.S. taxpayers who neglect to file Form 8938 face an initial penalty of $10,000, which can escalate to $50,000 for continued non-compliance following IRS notification. Additionally, a 40% penalty applies to any underreported tax linked to undisclosed foreign financial assets. If more than $5,000 in gross income from such assets is omitted, the statute of limitations may extend up to six years.

"Recalcitrant institutions will be punished with a 30% penalty on all US investments of their customers and the institution itself." – Michael Blicker, Senior Consultant, FICO

Non-compliant financial institutions may also face a 30% withholding tax on U.S. investments and payments. CRS penalties, which are enforced through national laws, often involve financial fines and increased audit risks imposed by local authorities. However, investors can avoid penalties by proving that any failure to disclose was due to reasonable cause rather than intentional neglect. For non-resident U.S. taxpayers who recently became aware of their obligations, the IRS offers streamlined filing compliance procedures. These allow individuals to catch up on filings without incurring the harshest penalties.

How FATCA and CRS Affect Global Investors

Identifying Reportable Accounts

Financial institutions rely on certain indicators to flag accounts that need to be reported under FATCA and CRS. These include clues like a foreign place of birth, a foreign residence or mailing address, or even an "in-care-of" address.

The reporting thresholds for FATCA and CRS differ significantly. Under FATCA, U.S. taxpayers must report foreign financial assets on Form 8938 if their value exceeds $50,000 on December 31 or $75,000 at any point during the year for single filers living in the U.S.. If you’re an American living abroad, these thresholds rise to $200,000 on December 31 and $300,000 at any point during the year. On the other hand, CRS typically has no minimum threshold for individual accounts, meaning even small balances can trigger reporting.

FATCA defines "specified foreign financial assets" broadly. This includes foreign bank accounts, stocks, securities, financial instruments, and interests in foreign entities like trusts or partnerships. However, there’s an important nuance: if you own foreign real estate directly, it’s exempt from reporting. But if the property is held through a foreign corporation or trust, you must disclose your interest in the entity.

Understanding these triggers is key to navigating compliance and protecting your assets.

Asset Protection and Compliance Strategies

Modern asset protection is all about transparency and legality. As Jim Bohm, a partner at Bohm Wildish & Matsen LLP, puts it:

"It’s still possible, but you can’t hide money offshore anymore – it has to be transparent and legal".

Here are some strategies to consider for safeguarding assets while staying compliant:

- Direct Ownership of Foreign Real Estate: Owning foreign property in your name avoids FATCA reporting, but holding it through a foreign entity requires disclosure.

- Private Placement Life Insurance (PPLI): This option lets high-net-worth individuals consolidate assets under an insurer, who is listed as the beneficial owner. This setup reduces public exposure and defers taxes.

For assets held through foreign entities (like corporations or trusts), disclosure is mandatory – even if direct ownership would have been exempt. To streamline reporting, assets already reported on forms like Form 5471 or Form 3520 don’t need to be listed again on Form 8938, but they still count toward your total threshold. When converting asset values to U.S. dollars, use the U.S. Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service foreign exchange rates as of December 31.

Certain items fall outside FATCA’s scope. Physical currency, off-bank precious metals, and personal effects like art or jewelry aren’t classified as "specified foreign financial assets". However, filing Form 8938 doesn’t replace the need to file an FBAR if your foreign accounts collectively exceed $10,000.

Conclusion

FATCA and CRS have reshaped the way offshore assets are managed. The days of hidden foreign accounts are long gone – both frameworks demand automatic reporting from financial institutions to tax authorities, leaving little room for undisclosed holdings. Falling out of compliance can lead to harsh financial penalties and withholding taxes, which could seriously affect your investments. This makes staying compliant not just important, but essential.

To safeguard your assets, proactive compliance is key. Keep your documentation up to date and promptly report any changes in tax residency. Under CRS, there’s often no minimum threshold for individual accounts, meaning even small balances can trigger reporting. If you manage assets through trusts, partnerships, or similar entities, financial institutions will "look through" these structures to identify controlling persons – typically anyone with 25% or more ownership. Be diligent with self-certification and update your information quickly, as institutions generally have a 90-day window to verify your details. High-value accounts may also be subject to enhanced scrutiny.

In this era of strict international regulations, systematic compliance is non-negotiable. With the complexity of these rules, seeking expert advice can help you navigate classifications and meet your obligations on time. Following official guidance can even shield you from penalties if errors arise later, as long as you acted in good faith.

Today, transparency and adherence to the law form the backbone of protecting international assets. By understanding your reporting responsibilities and adopting strong compliance practices, you can safeguard your offshore investments while aligning with global standards.

FAQs

What is the difference between FATCA and CRS?

FATCA (Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act) and CRS (Common Reporting Standard) serve similar purposes but differ in scope, jurisdiction, and reporting obligations.

FATCA, enacted by the U.S. in 2010, targets U.S. taxpayers holding financial accounts outside the country. It mandates foreign financial institutions (FFIs) to report detailed account information about U.S. persons directly to the IRS.

On the other hand, CRS, introduced by the OECD in 2014, establishes a global system for the automatic exchange of financial account data among participating nations. Unlike FATCA, which focuses solely on U.S. taxpayers, CRS applies to individuals and entities across multiple countries. FATCA is rooted in U.S. law, while CRS operates through multilateral agreements between nations.

Both systems share the goal of reducing tax evasion, but FATCA is designed specifically for U.S. compliance, whereas CRS supports a broader, international framework.

What changes to CRS in 2026 affect digital asset reporting?

The 2026 updates to the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) bring new rules for reporting digital and crypto-assets. These updates introduce tighter due diligence requirements, shorter timelines for reporting, and stricter expectations for data accuracy.

For financial institutions and taxpayers handling digital assets, staying compliant means adjusting to these heightened obligations. Getting a head start and fully understanding the changes can help reduce potential risks and make the reporting process more manageable.

What are the consequences of not complying with FATCA and CRS regulations?

Failing to meet FATCA and CRS requirements can carry heavy consequences. These might include hefty fines, withholding taxes, and other administrative penalties. Beyond that, non-compliance could attract extra attention from tax authorities and harm your financial reputation.

To steer clear of these issues, it’s crucial for investors to fully grasp their reporting responsibilities and ensure all required information is submitted accurately and on time. Compliance doesn’t just help you avoid fines – it also protects your global investments.