Remote work taxation just got more complicated. The OECD‘s November 2025 update to Article 15 introduces new rules for taxing cross-border remote workers. Here’s what you need to know:

- 183-Day Rule: Workers spending fewer than 183 days in a foreign country can avoid local taxes, provided their employer isn’t based there and no income is tied to a local permanent establishment (PE).

- 50% Threshold: Remote work exceeding 50% of total work time over 12 months may create a PE for employers, triggering host-country tax obligations.

- Commercial Purpose Test: A PE is only established if remote work supports business needs (e.g., managing local clients) rather than personal preferences.

- Employer Risks: Companies must track employee locations and document reasons for remote work to avoid unexpected tax liabilities.

- Employee Compliance: Remote workers must monitor time spent abroad to prevent double taxation.

These changes aim to address the complexities of remote work but add layers of compliance for both workers and employers.

1. Traditional Employees

For employees working in fixed locations like corporate headquarters, branch offices, or factory floors, the tax implications under Article 15 are relatively straightforward. The basic principle is this: if you work in a country, that country has the right to tax your employment income. At the same time, your home country may also tax you, but it usually provides a credit to prevent double taxation.

The 183-day rule offers an exemption in certain cases. It applies if you spend fewer than 183 days in the host country, your employer is not a resident there, and no part of your salary is tied to a local permanent establishment. However, this exemption is rarely relevant for traditional office workers. Why? Because fixed offices almost always qualify as a permanent establishment under Article 5. If salary costs are allocated to that location, the 183-day exemption is void.

For example, let’s say you spend six months working at your company’s London office. In this scenario, you’ll face immediate UK tax obligations. Only the income earned abroad will be subject to host-country taxation. To stay compliant with tax regulations, companies must carefully allocate salary costs to the correct jurisdiction.

"The 183-day rule is derived from three basic rules set forth in Article 15 of the OECD Model Tax Convention… employment income may be taxable in the country of residency if… the remuneration is not borne by a permanent establishment which the employer has in the other State." – Enrico Cecchini, Eca Italia

These rules highlight the clear tax challenges that traditional employees face when working in fixed locations. However, for remote workers, Article 15 presents a completely different set of hurdles.

2. Remote Workers

The OECD’s November 19, 2025 update sheds light on the unique tax challenges faced by remote workers under Article 15. A central concern is whether remote work in a foreign country creates a permanent establishment (PE) for employers. This framework distinctly separates the tax implications for remote workers from those of traditional employees.

A key guideline is that if remote work accounts for less than 50% of an employee’s working time over 12 months, it typically does not establish a PE for the employer . For instance, an employee working from home on a limited basis – less than half the time – generally avoids triggering PE status.

Even when the 50% threshold is met, a PE is only established if the remote work is tied to commercial purposes. Activities like managing local clients or suppliers can create a PE. However, if the remote work is driven by personal reasons – such as being closer to family or cutting down on commuting – it usually does not result in a PE . In other words, tax implications arise only when remote work is aligned with business needs rather than personal convenience.

Remote workers are also exempt from host-country taxes if they spend fewer than 183 days within a 12-month period in that country and no PE is established . If a PE is triggered, however, standard host-country tax rules apply, meaning the employer must meet local tax obligations.

Experts highlight that these updates are designed to minimize unexpected tax liabilities for employers. Still, businesses must carefully track where their remote employees are located and document the commercial reasons for their arrangements. The stakes are significant, as remote work is projected to shift around $40 billion in tax revenues between countries every year.

sbb-itb-39d39a6

Pros and Cons

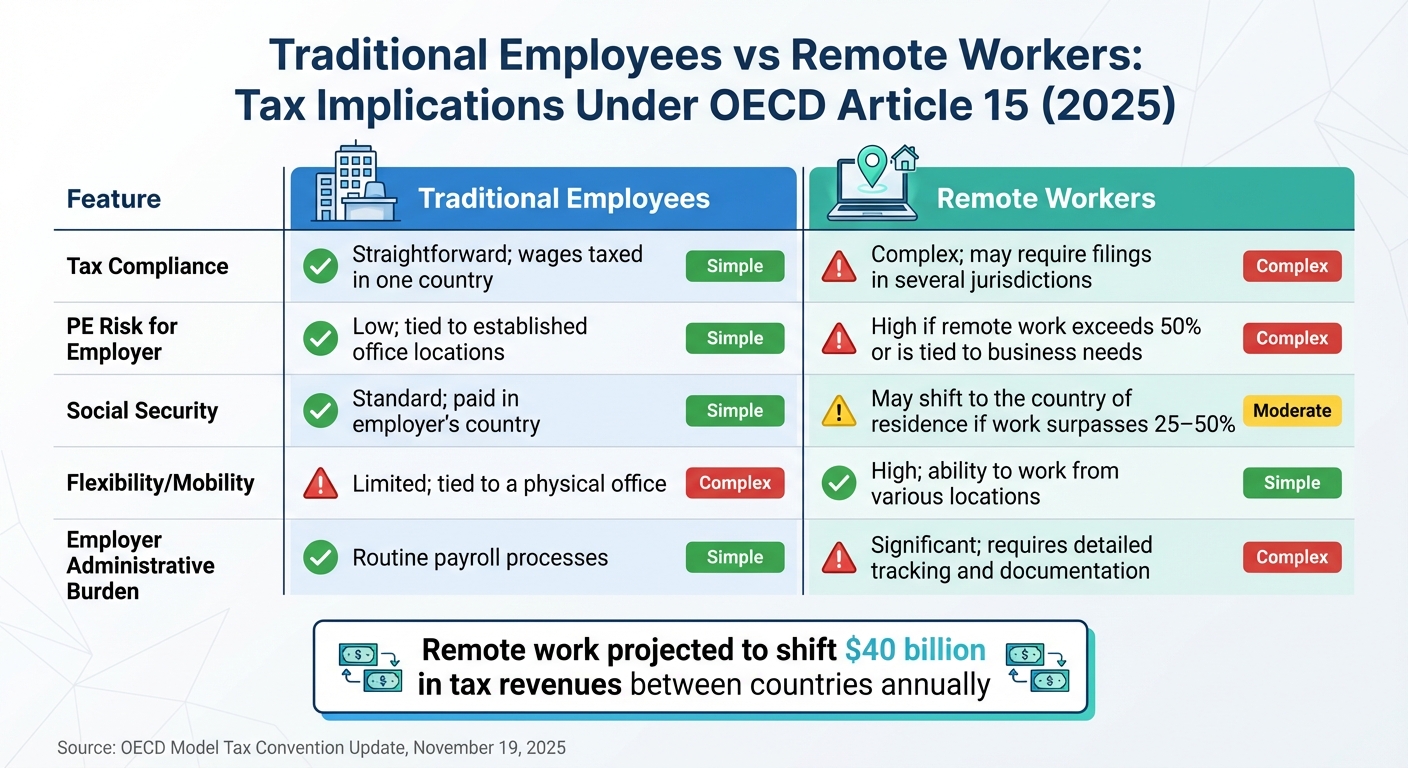

When comparing the tax implications for traditional employees versus remote workers, the 2025 update highlights some clear distinctions. Traditional employees generally benefit from simpler tax compliance processes. Their wages are taxed in one country, social security contributions are handled where the office is located, and there’s little risk of creating a permanent establishment (PE). On the other hand, remote workers face a more complex landscape, requiring significant effort to navigate intricate tax and social security rules.

Remote work does offer considerable flexibility, allowing individuals to work from various locations and potentially achieve a better work–life balance. However, this mobility comes with compliance challenges. Employers must carefully document whether remote work is "employer-driven" or "employee-driven", monitor the 50% threshold to avoid triggering a PE, and may even need to register for tax obligations in multiple jurisdictions.

| Feature | Traditional Employees | Remote Workers |

|---|---|---|

| Tax Compliance | Straightforward; wages taxed in one country | Complex; may require filings in several jurisdictions |

| PE Risk for Employer | Low; tied to established office locations | High if remote work exceeds 50% or is tied to business needs |

| Social Security | Standard; paid in employer’s country | May shift to the country of residence if work surpasses 25–50% |

| Flexibility/Mobility | Limited; tied to a physical office | High; ability to work from various locations |

| Employer Administrative Burden | Routine payroll processes | Significant; requires detailed tracking and documentation |

These differences highlight the trade-offs for both employers and employees. For employers, remote work offers access to a global talent pool but demands more rigorous compliance efforts. For employees, flexibility comes with the responsibility of tracking workdays and understanding tax obligations across borders.

As OECD Secretary-General Mathias Cormann remarked on November 19, 2025:

"By clarifying the rules for remote work and reinforcing source taxation for extractive industries, this update helps countries and businesses navigate a rapidly evolving global landscape".

However, it’s worth noting that some national laws may impose stricter requirements than the OECD guidelines. While employees enjoy greater mobility, they must remain vigilant about potential tax liabilities tied to their time spent abroad. Similarly, employers must balance the benefits of remote work with the administrative demands of compliance in multiple jurisdictions.

Conclusion

The 2025 OECD Model Tax Convention update, published on November 19, 2025, brings significant changes to how cross-border remote work is taxed. For traditional employees, the rules remain straightforward – their income is taxed where they physically perform their job, typically at their employer’s office. However, for remote workers and digital nomads, the update introduces a more intricate framework. Key changes include a 50% work-time threshold and a commercial purpose test, requiring remote workers to meticulously track their locations over a 12-month period.

If a remote worker exceeds the 50% threshold while performing work tied to commercial purposes, their employer could face permanent establishment (PE) obligations. Adding to the complexity, the UN Tax Committee is considering revisions to Article 15, which might expand taxing rights for home countries. This change could increase the likelihood of double taxation for remote workers.

On top of international guidelines, domestic tax laws can impose even stricter requirements. For instance, some countries may demand corporate tax registration at thresholds lower than those outlined in tax treaties. Additionally, certain taxes – like U.S. state income taxes – often fall outside the scope of double tax treaties, further complicating compliance. These overlapping rules create a maze of obligations that remote workers must carefully navigate.

To tackle these challenges, thorough tax planning is essential. Remote workers should seek professional advice to properly document their work arrangements and monitor threshold limits, helping them avoid unintended double taxation. Services such as those offered by Global Wealth Protection are designed to assist location-independent professionals in crafting detailed strategies to manage cross-border tax responsibilities, optimize their tax situation, and ensure compliance across jurisdictions.

The complete revisions to the OECD Model Tax Convention are expected in 2026. As these rules continue to develop, remote workers should stay updated and consult experts to adapt to the evolving tax landscape.

FAQs

How does the 183-day rule impact taxes for remote workers?

The 183-day rule is a key factor in determining if a remote worker’s income becomes taxable in a foreign country. Essentially, if you spend 183 days or more in another country within a tax year, that country typically has the right to tax your income under Article 15 of the OECD Model Tax Convention. In this case, your earnings are considered taxable where they are generated.

On the other hand, if your stay in the foreign country is less than 183 days, your income is generally only subject to taxation in your home country (your country of residence). That said, specific tax treaties between countries can create exceptions, so it’s crucial to check the agreements relevant to your situation.

What conditions create a permanent establishment for employers with remote workers?

A permanent establishment (PE) can be created when a remote employee’s work leads to a fixed place of business in another country, such as consistently using a home office for work. Moreover, if the employee acts as a dependent agent – someone with the authority to negotiate or finalize contracts on behalf of the employer – this could also result in a PE.

According to the OECD, spending more than 50% of work time in a foreign location may increase the likelihood of establishing a PE. To avoid unexpected tax liabilities in other countries, employers should thoroughly assess the responsibilities and activities of their remote employees.

How can remote workers avoid being taxed twice under the updated OECD rules?

Remote workers can sidestep double taxation under the 2025 OECD updates by following a few essential steps:

- Keep your tax residency in your home country: Limit the amount of time you work in other countries to avoid triggering tax obligations there. Spending too much time in another jurisdiction could lead to unexpected tax consequences.

- Avoid creating a permanent establishment (PE) for your employer: A home office or second-home setup usually doesn’t count as a PE unless you regularly finalize contracts or spend more than half your working days in that location.

- Stick to the 183-day rule for employment income: Under Article 15, if you work fewer than 183 days in another country, your income typically remains taxable only in your home country. If you do pay taxes abroad, many double-tax treaties allow you to claim a credit or exemption.

Keeping thorough documentation is key. Maintain records like employment contracts, daily logs of where you work, and evidence that your employer doesn’t have a dependent agent in the host country. These details can prove compliance and help you avoid double taxation headaches.