Tax residency determines where your offshore company is taxed, and it’s not just about where the company is incorporated. Factors like where management decisions are made, where operations take place, and where contracts are signed can all impact tax residency. Misjudging this can lead to unexpected tax bills, penalties, or even double taxation. Here’s what you need to know:

- Key Determinants of Tax Residency:

- Place of Incorporation: Some countries tax companies based on where they’re registered.

- Central Management and Control: Where key decisions are made often dictates residency.

- Permanent Establishment: Having offices, employees, or operations in a country can trigger tax obligations.

- Offshore Taxation Basics:

- Zero-tax jurisdictions (e.g., Cayman Islands) don’t impose corporate taxes, but compliance with local rules is required.

- Territorial tax systems (e.g., Hong Kong) only tax income earned locally, not foreign-sourced income.

- Challenges for Business Owners:

- U.S. citizens face worldwide taxation and must report offshore profits under Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules.

- Dual residency conflicts can arise when two countries claim the same company, often resolved through tax treaties.

- How to Manage Tax Residency:

- Align operations with your desired tax residency through careful planning.

- Document board meetings, decision-making locations, and compliance with economic substance laws.

- Regularly review your structure to adapt to changing tax laws and business activities.

Tax residency is complex, but proper planning ensures compliance and minimizes tax exposure. Understanding these rules is essential for anyone operating offshore companies.

How Tax Residency Rules Work for Offshore Companies

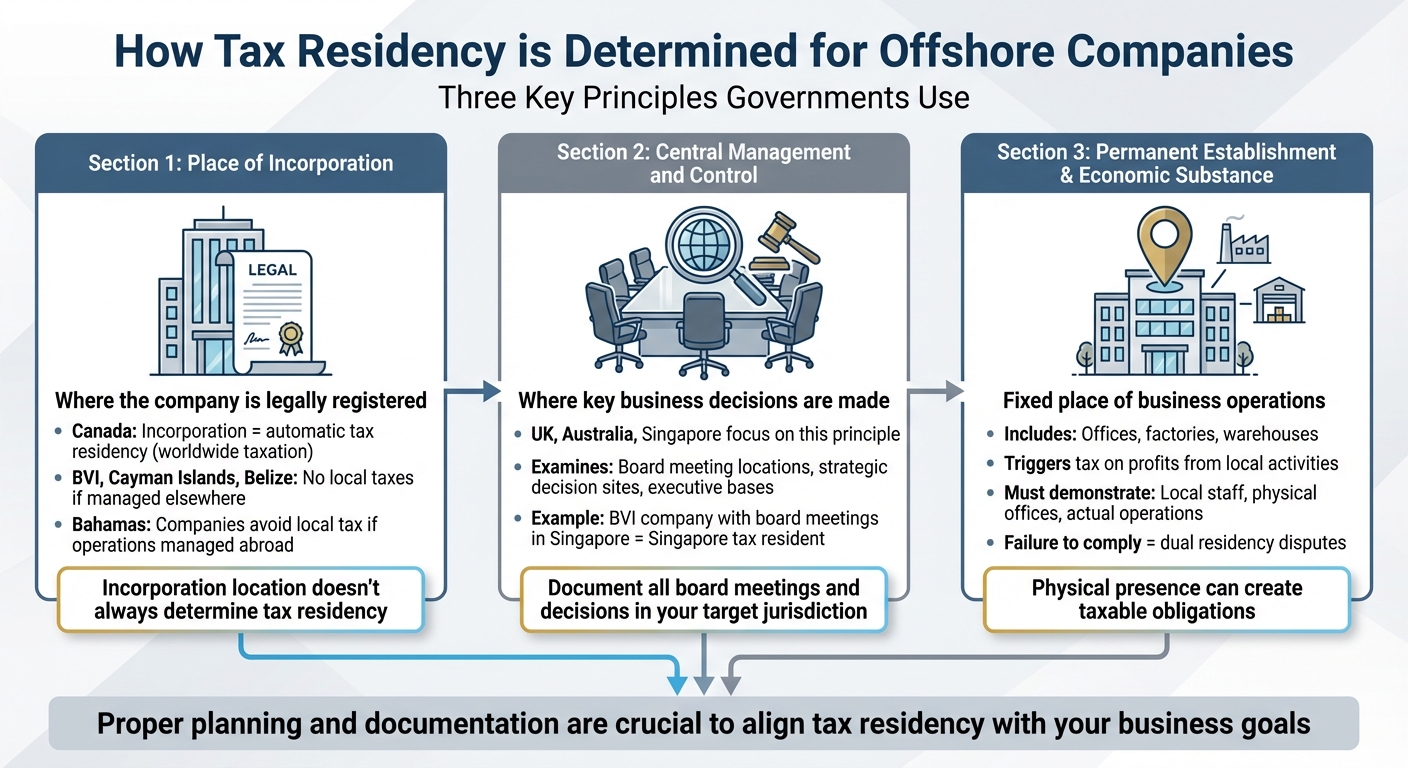

Governments use three main principles to determine an offshore company’s tax residency: place of incorporation, central management and control, and permanent establishment with economic substance. Here’s a closer look at each of these criteria and how they influence tax residency.

Place of Incorporation

Some countries determine tax residency solely based on where a company is legally incorporated. For example, in Canada, incorporation automatically establishes tax residency, meaning the company is subject to worldwide taxation – even if its management operates from another country.

However, many offshore jurisdictions take a different approach. Tax havens like the British Virgin Islands (BVI), Cayman Islands, and Belize do not impose local taxes on companies incorporated there, provided their management and control occur elsewhere. Similarly, under the Bahamas‘ International Business Act, companies incorporated there can avoid local taxation if their operations are managed abroad. Essentially, while the place of incorporation is important, it doesn’t always determine tax residency on its own.

Central Management and Control

Tax residency often hinges on where a company’s key decisions are made. Jurisdictions like the UK, Australia, and Singapore focus on the location of central management and control to establish tax residency. This involves examining where the board of directors meets, where strategic decisions are finalized, and where senior executives are based.

For instance, if a BVI company holds its board meetings and makes strategic decisions in Singapore, it may be considered a Singapore tax resident. To ensure tax residency aligns with your intended jurisdiction, it’s essential to conduct board meetings and make key decisions in that location, backed by proper documentation.

Permanent Establishment and Economic Substance

A permanent establishment (PE) refers to a fixed place of business – such as an office, factory, or warehouse – through which a company operates in a specific country. If your offshore company has a physical office or employs representatives who regularly sign contracts in a country, that country may claim the right to tax profits tied to those local activities.

Additionally, economic substance rules require companies to demonstrate actual business operations, such as employing local staff or maintaining physical offices, to validate their tax position. Failing to meet these substance requirements can lead to disputes, including dual residency claims, which may require resolution under tax treaties. Proper planning and compliance are crucial to avoid such complications.

How Tax Residency Affects Offshore Company Taxation

Understanding tax residency is crucial when it comes to shaping your offshore company’s tax obligations. Once you identify where your company is considered tax resident, the next step is figuring out how that impacts your tax liability. Tax residency determines which countries can tax your profits and how much you might owe. This depends on three main factors: the tax rules of the offshore jurisdiction, the tax laws in your home country, and any applicable tax treaties.

Taxation in Offshore Jurisdictions

In zero-tax jurisdictions like the British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, and Bermuda, corporate income tax is nonexistent. But "zero tax" doesn’t mean there are no costs or obligations. These jurisdictions often charge annual registration, license, and government fees, which can range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars. Additionally, companies are typically required to maintain basic accounting records and file annual returns, even if no tax is owed.

Jurisdictions with low-tax or territorial systems operate differently. In these systems, only income earned within the jurisdiction is taxed, leaving foreign-source income untaxed at the corporate level. For example, if your offshore company earns all its revenue from clients outside the jurisdiction, the local tax rate on those profits might effectively be 0%. However, any income sourced locally – such as payments from local clients or profits from a local office – would still be taxed at standard rates.

A major development in recent years is the introduction of economic substance requirements. Many traditional offshore jurisdictions now mandate that companies engaged in specific activities, like holding assets or managing intellectual property, demonstrate a real local presence. This includes having local directors, employees, office space, and conducting core business activities within the jurisdiction. Failing to meet these requirements can lead to penalties, denied tax benefits, or even automatic information sharing with foreign tax authorities, which could trigger tax claims in other countries.

Taxation in the Owner’s Home Country

Your personal tax residency and your home country’s tax laws play a critical role in determining your overall tax liability. Offshore structures often face challenges when high-tax countries like the United States tax their residents on worldwide income, regardless of where the company is incorporated. For instance, if you’re a U.S. citizen or resident, the IRS will tax your offshore company’s profits, even if the company pays no tax in its jurisdiction of incorporation.

The U.S. enforces these rules through Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) regulations, which include Subpart F income and GILTI (Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income) provisions. These rules can require you to report and pay U.S. tax on certain offshore profits – especially passive income like interest, royalties, and dividends – even if those profits are not distributed to you as dividends. Essentially, U.S. taxpayers cannot defer taxes by keeping profits in a low-tax offshore entity.

Other high-tax countries, such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and many EU nations, have similar CFC rules. While the specifics differ, the outcome is often the same: your personal tax residency often outweighs your company’s tax residency when determining your final tax bill.

If your offshore company is considered a U.S. tax resident because its management occurs within the U.S., it may face U.S. corporate tax on worldwide income. On top of that, you could still face shareholder-level taxation on distributions. This double taxation can wipe out any potential benefits of operating offshore.

Dual Residency and Tax Treaties

When two countries both claim your offshore company as a tax resident, dual residency conflicts arise. For example, a company incorporated in a zero-tax jurisdiction but managed and controlled from a high-tax country (where board meetings and key decisions take place) could be treated as a tax resident in both jurisdictions. This could lead to taxation on worldwide income in both countries, along with duplicate filing requirements and increased compliance costs.

Tax treaties help resolve these conflicts. Most treaties include tie-breaker rules to assign tax residency to one country, typically based on the place of effective management – where the company’s daily operations and strategic decisions are carried out. Once residency is determined under the treaty, the other country usually steps back from taxing worldwide income, though it may still tax locally sourced income.

Treaties also help minimize withholding taxes on cross-border payments and provide mechanisms to avoid double taxation. However, to access these benefits, your offshore company will often need a Tax Residency Certificate (TRC) from the jurisdiction where it is considered resident. Without proper documentation and meeting substance requirements, tax authorities may deny treaty benefits, exposing your company to higher taxes and increased scrutiny.

How to Manage Offshore Company Tax Residency

Managing your offshore company’s tax residency isn’t just a one-time task – it’s an ongoing process that requires careful planning, thorough documentation, and regular reviews. To ensure compliance and achieve your desired tax outcomes, you need to align your corporate structure, governance, and operations with the tax rules of each jurisdiction that could potentially claim your company as a resident.

Mapping Your Company’s Footprint

Start by documenting your company’s tax footprint. This means identifying where your company is incorporated, where its central management operates, and where it has permanent establishments or main offices. Each of these elements can independently trigger tax residency in a specific jurisdiction.

For example, if a company incorporated in the Cayman Islands is managed from another country, its tax residency shifts to that location. Similarly, a BVI company managed from Singapore becomes a Singapore tax resident, which might exempt it from BVI economic substance requirements if it’s considered non-resident in the BVI.

Keep detailed records of board meeting locations, key decision-making points, and where directors are based. Document board minutes, director contracts, and any activities tied to setting company policies. If your company has physical offices or representatives signing contracts in a specific location, this could establish a "permanent establishment", which might lead to a taxable presence in that jurisdiction. For instance, a Cayman Islands company running a restaurant in London would be subject to UK taxes on income earned in that location.

Once your company’s footprint is clearly mapped, you can adjust its governance to align with your tax residency goals.

Structuring Management and Operations

After understanding your footprint, take steps to structure your company’s management in a way that supports your residency objectives. If your goal is to establish tax residency in an offshore jurisdiction like the BVI or Cayman Islands, ensure that board meetings and decision-making activities occur there. Appointing local directors can further solidify your company’s residency status.

Avoid running your company from high-tax jurisdictions like Canada, the UK, or Australia, as these countries determine tax residency based on where central management and control are exercised, not just where the company is incorporated. Using nominee directors, holding virtual board meetings in the offshore jurisdiction, and limiting physical operations in high-tax countries can help maintain your desired residency. However, remember that personal tax rules may still apply depending on your individual circumstances.

In jurisdictions that require a local presence to meet economic substance laws, make sure your company has the necessary staff, office space, and real business activities in place. Failing to meet these requirements could lead authorities to disregard your company’s structure and directly tax the income as if it were yours.

Once your management and operations are aligned, focus on meticulous documentation to back up your residency claims.

Ensuring Compliance and Documentation

Strong documentation is essential for substantiating your company’s tax residency. Maintain detailed records such as board meeting minutes, director agreements, and filings that demonstrate compliance with economic substance requirements. Keep copies of annual returns, financial statements, and any Tax Residency Certificates (TRCs) issued by the jurisdiction where your company is registered.

Non-compliance with economic substance laws could result in authorities sharing information with your home country, potentially triggering Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules. This could lead to your company’s profits being taxed directly in your home country.

"Minimize or avoid exit taxes when leaving a high-tax country: plan 12–24 months ahead, restructure assets, use tax treaties, pick a low-tax residency, and consult experts." – Global Wealth Protection

Conduct an annual review of your company’s structure. Tax laws are constantly changing, and your business activities may evolve over time. Regularly auditing your company’s footprint can help you identify and address potential residency risks before they turn into liabilities. If you’re expanding operations or moving into new jurisdictions, update your records accordingly. Seeking professional advice can also help you navigate dual residency issues and avoid unintentionally creating permanent establishments in places you’d rather not be taxed.

sbb-itb-39d39a6

Tax Residency Optimization Strategies for Offshore Companies

Once you’ve mapped out your company’s operations and structured them effectively, the next step is to implement strategies that can help reduce tax obligations. The key here is to make the most of residency rules while fully complying with both offshore and home-country regulations. These strategies rely on thorough documentation and careful operational planning.

Using Non-Resident Offshore Jurisdictions

Certain jurisdictions allow companies to separate their place of incorporation from their tax residency. For example, in places like the BVI, Cayman Islands, or Belize, a company can be incorporated locally but treated as non-resident for tax purposes if its central management and control are conducted abroad.

To maintain non-resident status, ensure that directors and decision-makers operate from overseas, that board meetings are held outside the jurisdiction, and that key operational activities occur abroad. Additionally, avoid creating tax residency in high-tax countries by steering clear of activities like maintaining a fixed business location or employing staff who regularly negotiate or sign contracts locally.

For U.S.-based entrepreneurs, this often means appointing independent directors in jurisdictions with strong treaty networks and implementing strict internal policies requiring contracts to be approved and signed offshore. U.S. taxpayers should also pay close attention to compliance rules, such as Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) regulations and Form 5471 filing requirements.

Territorial tax systems offer another way to reduce tax burdens on foreign-sourced income.

Using Territorial and Exemption Tax Systems

Territorial tax systems only tax income earned locally, leaving foreign-sourced income largely untaxed. Jurisdictions like Hong Kong, Singapore, Panama, and certain UAE setups follow this model, offering significant tax advantages for businesses with foreign income.

For example, an offshore company engaged in cross-border consulting, intellectual property (IP) licensing, or online services can structure its operations to classify profits as foreign-sourced. This setup might include managing operations and banking in a way that avoids local taxation. Take an online software company with customers in North America and Europe: if its servers and staff are located outside the territorial-tax country, its income might qualify as foreign-sourced, resulting in little to no local corporate tax. At the same time, the company benefits from operating in a well-regarded jurisdiction with access to tax treaties.

For this strategy to work, it’s essential to position customer contracts, key functions, and risk-taking activities outside high-tax regions. Transfer pricing must align with arm’s-length principles, and local substance requirements need to be met. Obtaining tax residency certificates from the jurisdiction can also help claim treaty benefits and defend the structure.

While these methods can reduce tax liabilities, it’s equally important to navigate anti-avoidance measures effectively.

Avoiding Anti-Avoidance Rules

Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules can attribute certain passive or low-taxed active income from an offshore company directly to its resident shareholders, even if the profits remain undistributed. For U.S. taxpayers, a foreign corporation is classified as a CFC when U.S. shareholders (each holding at least 10% of the vote or value) collectively own more than 50% of the company. This triggers annual taxation on the company’s Subpart F and GILTI income, with the possibility of foreign tax credit relief.

General Anti-Avoidance Rules (GAAR) also allow tax authorities to disregard arrangements that lack genuine commercial substance. Common red flags include mailbox companies, circular financing without a true business purpose, and profit-shifting through nominee arrangements.

To meet GAAR and economic substance requirements while optimizing taxes, your offshore structure should serve a legitimate commercial purpose. This could include proximity to regional markets, regulatory stability, access to specialized talent, improved banking services, or legal certainty. You’ll also need to demonstrate adequate economic substance, such as maintaining physical office space, employing staff or contracted management, and having an active board with local directors.

Proper documentation of intercompany transactions is crucial, especially when dealing with intellectual property, financing, or services. Transfer pricing should accurately reflect the value of these transactions. Passive holding companies in traditional tax havens with concentrated U.S. ownership are particularly vulnerable to CFC taxation and GAAR scrutiny.

Conclusion

Tax residency determines the tax rules your business must follow, which often differ from the place where your company is incorporated. To avoid complications, your business practices must align with key residency tests – such as incorporation, management, and permanent establishment. Missteps here can lead to your offshore company being taxed in multiple countries, exposing you to double taxation risks unless you’ve accounted for tax treaties in your planning. This highlights the importance of careful residency planning to balance tax efficiency with regulatory compliance across borders.

For U.S. residents, worldwide income is subject to taxation. Offshore companies don’t exempt you from U.S. tax obligations on profits, dividends, or capital gains. Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules can attribute passive or low-taxed offshore income directly to your U.S. tax return. Even if your offshore jurisdiction imposes no corporate tax, U.S. reporting requirements – like entity disclosures, foreign bank account reports, and ownership forms – remain mandatory, with severe penalties for non-compliance. A well-structured offshore plan is essential to navigate these complexities.

Legitimate offshore planning emphasizes legal tax optimization and strict adherence to compliance. Effective strategies might include using non-resident offshore jurisdictions where management occurs outside the U.S., leveraging territorial tax systems that exclude foreign-sourced income, and ensuring your structure meets anti-avoidance rules by maintaining real economic substance. Proper documentation to support your residency status is critical. Regular reviews with international tax experts can help you stay compliant with evolving regulations. Keeping up with these changes is vital for long-term success.

As tax residency and economic substance rules grow more stringent, proactive planning becomes even more crucial. Significant business changes – like relocating key managers to the U.S., opening a new office abroad, or entering a new market – should prompt an immediate residency impact analysis to manage tax exposure effectively. Specialized firms such as Global Wealth Protection offer services tailored to location-independent entrepreneurs and investors, including offshore company formation, U.S. LLCs, offshore trusts, and tax optimization strategies that align residency planning with business realities and compliance for both U.S.-based and international clients.

Offshore companies can be powerful tools for international trade, asset protection, and tax planning – provided they comply with all legal and reporting requirements. By intentionally aligning your company’s incorporation, management, and substance with clear business purposes, you can achieve predictable tax outcomes, benefit from favorable treaties, and reduce overall tax burdens – all while staying within legal boundaries. The key is transparent, well-documented planning, supported by professional guidance to strike the right balance.

FAQs

How do I figure out the tax residency of my offshore company?

The tax residency of an offshore company is determined by the regulations of the jurisdiction in which it operates. This often hinges on where the company is managed and controlled – meaning the location of board meetings, where key decisions are made, and where core management activities take place.

To navigate this complex area and ensure compliance, it’s essential to work with legal and tax experts who specialize in international laws. Their guidance can help you make well-informed decisions tailored to your company’s needs.

What challenges can dual tax residency create for offshore companies?

Dual tax residency presents a host of challenges for offshore companies, often leading to increased tax burdens and the potential for double taxation. This happens when two countries assert the right to tax the same income, creating overlapping obligations that can strain a company’s finances.

On top of that, managing the compliance demands of two separate tax systems can be both complicated and time-intensive. Companies may also encounter legal disputes between jurisdictions, adding another layer of difficulty and driving up operational costs. To navigate these hurdles effectively, thorough planning and guidance from experts are crucial to reduce risks and maintain compliance.

What are economic substance requirements, and how do they affect offshore tax planning?

Economic substance requirements are designed to ensure that offshore companies engage in genuine business activities within their jurisdiction. This involves maintaining real operations, employing local staff, or owning physical assets in the area, rather than functioning as mere "paper companies."

These regulations have a noticeable effect on tax planning. They increase compliance responsibilities and restrict the use of artificial setups aimed at minimizing taxes. While this can lead to higher operational expenses, it also promotes greater transparency and aligns with global efforts to curb tax evasion.