After 20 years the SCOTUS agrees to hear a case regarding asset forfeiture. The ruling could introduce some checks and balances to a very corrupt and devastating government scheme.

July 2, 2018

By: Bobby Casey, Managing Director GWP

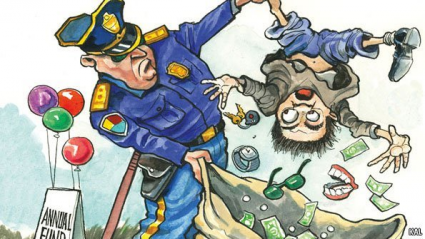

In an article written a little over a year ago, we pointed out that the DEA has stolen over $4.15 billion in cash alone through this scheme. The real kicker: over 80% of those seizures were never connected to any criminal charges. What is even worse, the very defense for this scheme is to stop criminal activity such as drug trafficking and money laundering. But if 80% of the take isn’t tied to a crime, then how is this the effective crime-fighting tool the DOJ insists it is?

While we are seeing a hopeful change on the state level toward civil forfeiture, the feds are not nearly as eager to give up the practice. America held its breath, waiting for the opportunity to be heard by the SCOTUS, and the moment has finally arrived!

For the first time in about 20 years, on the grounds that it violates the 8th amendment of the constitution, the SCOTUS will hear The State of Indiana v Tyson Timbs. It’s unfortunate someone has to be raked across the coals as an example first in order to interpret the laws of the land, but perhaps this will not be in vain.

Tyson Timbs was compelled to forfeit a Land Rover worth $40,000 after pleading guilty to selling $200 worth of drugs (4 grams of heroin). The Land Rover was purchased with life insurance money he received after the passing of his father. He had already agreed to house arrest and $1,200 in court fees, but the state also came after his car.

Timbs successfully disputed this convincing a trial judge that the forfeiture was “grossly disproportional”. Even with a felony conviction, the maximum fine would be $10,000 which is only a fraction of the car’s value. An appellate court then upheld that ruling. It wasn’t until his case got before an Indiana Supreme Court that the decision was reversed:

“’The Excessive Fines Clause does not bar the State from forfeiting Defendant’s vehicle,’ the court ruled, ‘because the United States Supreme Court has not held that the Clause applies to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment.’”

Here’s the verbiage of the 14th amendment:

“No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

There are a good number of judges who have written admonishing opinions on the matter of civil forfeiture, contending even that civil penalties often exceeded that of compensatory or restorative costs, and go further in crippling the livelihoods of these offenders. In the case of Timbs, taking his car, for example, makes it impossible for him to fulfill his own court order of attending rehabilitation meetings or finding a job.

There have been some hopeful cases heard as well that have favored doing away with such egregious and harsh civil penalties so the fact that the SCOTUS is willing to even hear this case is a tremendous step in the right direction!

Meanwhile, there are a good number of people who are relying on a positive ruling from this court. People like Rustem Kazazi, who was traveling with his entire life savings back to Albania to restore an old family home. According to the Institute for Justice:

“U.S. Customs and Border Protection took Kazazi into a small interrogation room, stripped him naked for a full-body search, interrogated him without a translator, and then seized his family’s life savings of $58,100 without charging anyone with a crime.”

There’s also a nurse out of Texas who is originally from Nigeria: Anthonia Nwaorie. She also saved up a goodly sum of money in the hopes of starting a medical clinic for mothers and children in her native country. Customs and Border Patrol seized $41,377 from Anthonia, denied her day in court and then had the nerve to offer her money back if she signed a waiver absolving CBP of any wrong-doing.

Gerardo Serrano lost his truck to CBP because he forgot there were 5 bullets still in the console when crossing the border from Mexico. The border agents let him go, as he was not charged with a crime. But the agents kept the Ford F-250 since it was used to transport “munitions of war”. Not only did he have to pay $3,800 to contest the seizure, but he had to continue making the payments of the truth while it sat in impound for 2 years. While he got his truck back in 2017, he is still in a major class action suit with others who found themselves in a very similar predicament but were not as lucky to get their vehicles returned.

When reading some of these cases I wonder what prevents any state agent from just seizing anything and everything on your person for no stated reason? How is this not the contemporary iteration of the Divine Right of Kings?

The incredibly scary realization is what can happen in the absence of any accountable, consistent, and necessary due process. A similar question was posed regarding the lack of due process for undocumented migrants:

Question: What’s to stop ICE from detaining Americans?

Answer: Well, they could easily prove they were citizens.

Question: Without due process, how, where, and to whom would they prove this?

Framing this back in the context of asset forfeiture, can you prove you acquired this money legitimately? Great! How, where, and to whom if there’s no due process? And if you are acquitted or never charged criminally, can you convince, not a judge, but often a prosecutor, that they shouldn’t keep those assets?

The implications of holding states and local municipalities to the standards beset by the Constitution are myriad. Think about what it means in terms of sentencing structures at the state level:

Traffic ticket fines: does every ticket really warrant several hundred dollars in fines? And if you can’t pay you potentially wind up in a modern-day debtors’ prison?

Mandatory minimums for possession of a controlled substance. Is being caught with a few ounces of weed deserving of ruining a person’s ability to get a job and incarcerating them for a minimum number of years?

This case won’t be heard until the end of this year with a likely adjudication early 2019. Moreover, it wouldn’t mean the END of asset forfeiture. It would just be the end of excessive asset forfeiture.

Click here to schedule a consultation or here to become a member of our Insider program where you are eligible for free consultations, deep discounts on corporate and trust services, plus a wealth of information on internationalizing your business, wealth and life.

If the Supreme Court had an ounce of sanity, it would recognize that the state already has the power to enforce fines; as such, there would be no need for them to also enforce civil penalties via civil asset forfeiture. They would also recognize that “service” cannot properly be served against an inanimate object, like a car or truck; it can only be served upon the owner. And since the state gets to take possession (via seizure) of the object in question before the case is even adjudicated, it amounts to the owner having to prove their innocence, so they are deemed guilty until proven innocent. This is against the logic of the entire judicial system of the United States.

I agree with all of this… and the lynchpin of it all is, as you say, “sanity”. LOL Asset forfeiture from a criminal standpoint makes some sense in that it could serve as evidence in a criminal case. But civil forfeiture never made any sense to me. How the heck is someone’s house involved in a crime… while the owner isn’t? How does that even work? It doesn’t obviously. But any port in a storm. If this serves as a catalyst to ending or at least reducing asset forfeiture, then it’s better than the status quo.